I take a bus alone from Panama City into the jungle. One one-way ticket. My friend Guadalupe, a retired Spanish journalist who has been my tropical partner-in-crime for three months has returned to Spain, leaving me with a kiss on each cheek and a warning to stay safe.

The crowded bus terminal across from Albrook, a famous mall on the outskirts of Panama City is a disorganized Port Authority on acid. The old bus I board looks like something out of a Bollywood movie meets a Grateful Dead tour van from the 1960’s revamped for everyday travelers. All brocaded curtains, paisley patterned seats, gold, red, and psychedelic purple swirling over the interior.

We drive five hours through small towns nestled in palm trees, a trek that oddly reminds me of when I was in love with a girl in Toronto and would regularly take the endless bus ride from NYC through Upstate New York and across the Canadian border to see her. Youthful amor knows no geographical boundaries.

Now, waiting for me is a cheerful older ex-pat named Kippy, with short cut blonde hair and a gap-toothed grin in her beat up old truck blasting jangling Motown.

“We’re going to a party.” She announces, as I climb in.

When Guadalupe was here, I was able to hang out with Panamanians, the feisty ninety-four year-old matriarch of the small town Pedasi, an owner of a hostel who called me “Mi Rei,” my king, a guy from Chile who strummed guitar while I belted live karaoke in his cantina, American songs like House of the Rising Sun, Proud Mary and Mack The Knife. It seems now that Guadalupe is gone, that world is inaccessible to me. So I fall in with the expats.

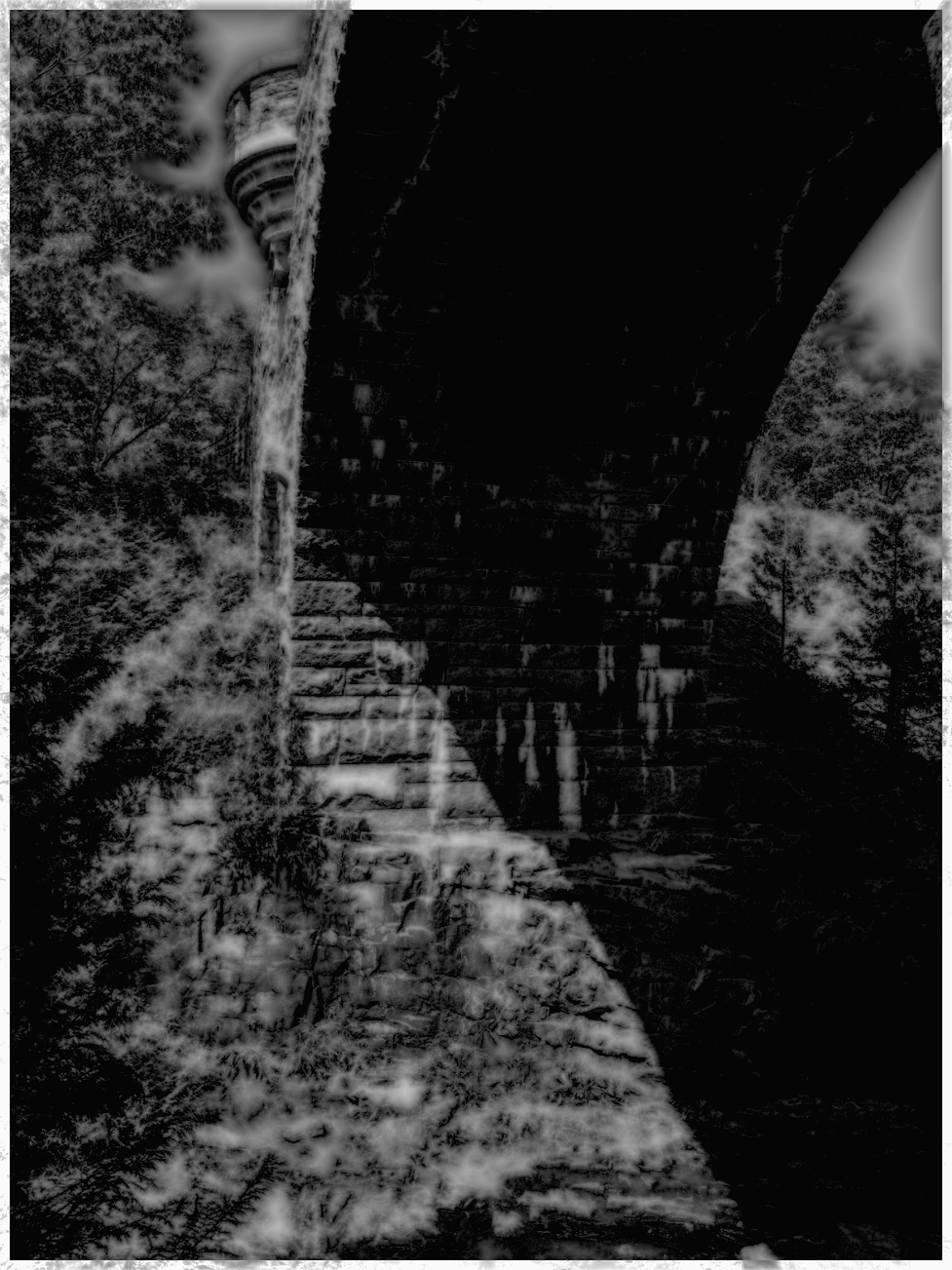

After the concrete condos of Panama City, rising by the Pacific like some Miami Vice throwback, the cracked sidewalks and salt stung air, window washers rushing out at streetlights with homemade squeegees and buckets of sudsy water like the crackheads on Houston Street did when I was a kid, the countryside feels even more surreal and tranquil. Kippy and I stop at a roadside stand to buy giant bunches of pinkly stained lychees, and semilla de coco a new delicacy for me, a round white orb of coconut seed with a spongy texture and pure subtly sweet flavor.

On the beach, under the portico of a local cantina, a group of expats have gathered to party, throwing back rum and $1 beers. I haven’t been around this many white people in months and it feels overwhelming and a bit embarrassing. They form their own cohort and even though many have lived in the country for years, they don’t speak Spanish. I wonder how they go grocery shopping.

All the expats in the jungle by the sea seem to have ended up here for some shady reason. So have I, I suppose. No one leaves everything they know behind unless they want to escape something.

At her seventy-first birthday party on the beach, I meet Corey, a “California girl” and old school lesbian who tells me she used to have a gambling problem.

“What made you stop?” I ask.

“I lost my job and my house.” She says frankly, in her nicotine growl, going off to chain smoke another menthol.

There is Sammy, who arrives at the beach and immediately announces he has just gotten a blood test for HIV and herpes.

“I met someone.” He says giddily. “I’m doing it for her.”

After our third round of cervezas, I find out he is a New York Jew, like me, though originally from Israel and three decades older.

He and his parents emigrated to the Bronx of the 1950’s when he was a kid, then moved to Canada when he turned eighteen, so he wouldn’t be drafted in Vietnam.

“When I was eight years-old I got held up by knifepoint for milk and eggs I was bringing home to my mom.” He says.

He notices me noticing his tattoos, numbers across his inner arm and a semi-colon at his hairy wrist.

“The numbers were my father’s when he was in a camp. The semi-colon you should know as a writer.” He says.

“I do.” I say. “But what does it mean to you?”

“My son committed suicide two years ago. It means continuation. Life continues.” He says.

The sun sets over the sea and the green hills of Isla Iguana in the distance. The island looks so close under the bronze, violet and blood red rays it seems you could swim there, though you would die trying.

Terrible news filters in from the States. There is a certain anarchy among the ex-pats, escapees who have given up their country for another. Some try their best to ignore all American news, some rage against it. But all seem to live in a sort of tropical Brigadoon, a valley the outside world can’t penetrate.

It reminds me of an ill-timed trip my grandparents took me and my brother on my senior year of high school in 2003. We ended up in the Galapagos Islands on a small nature cruise touring islands desolate except for teeming wildlife.

On one of the few inhabited spots in the archipelago in a small internet café, I found out through an email from my dad that the United States had declared war in Afghanistan. Only two years after 9/11 had changed my New York childhood and teenage world forever, I cried in a roughly paved town square thousands of miles from home feeling angry and helpless all over again. War was the last thing I wanted, but how could I stop it?

Fifteen years later, on a different beach, someone makes a crack about sexual assault on the darkened porch. An older gay man talking about the priests of his youth molesting fellow choir boys.

“The whole time, I was like pick me! Pick me! Is something wrong with me that they don’t want to fuck me?” He says and everyone laughs uproariously.

I don’t and get sideways glances like I’m being a party pooper.

“I think it’s normal for kids to feel chosen or made special by abusers.” I say. “That’s part of the abuser’s power over their victims. I’m sorry you felt that way.” I tell him.

And as the chuckles around us fade, he nods quietly and says, “Thank you.”

“When I was a teenager we fooled around, but we were just figuring out what we liked and what we didn’t.” Protests a grandmother from Colorado. “If a boy and I were heavy petting and he did something I didn’t like, I always told him ‘no,’”

Though unstated, it is clear we are now talking about the recent hearings around the latest Supreme Court nominee.

“There’s a difference between normal exploration and being forced into a situation.” I tell her. “Some people don’t have the ability to say no while it’s happening, that doesn’t make it okay.”

“What about innocent until proven guilty?” She jabs.

“What about believing victims?” I ask.

“I was never a victim.” She says so vehemently it makes me wonder, if like the joke about the priests, there is some pain behind her bluster.

“Bet you didn’t think hanging around with a bunch of old people, you’d be having conversations like this.” Kippy takes me aside to order us more drinks.

“I spoke to my dad on the phone the other day about his artwork and how he used to correspond with a guy who was into phallic piercings to do a portrait.” I shrug. “He’s older than all of you.”

But as the party dies down, I think about generational ideas of sex. How this older crew who grew up with so much normalized repression and sexism have all been touched by abuse in some way and see it as a hard knock reality rather than something that needs to change.

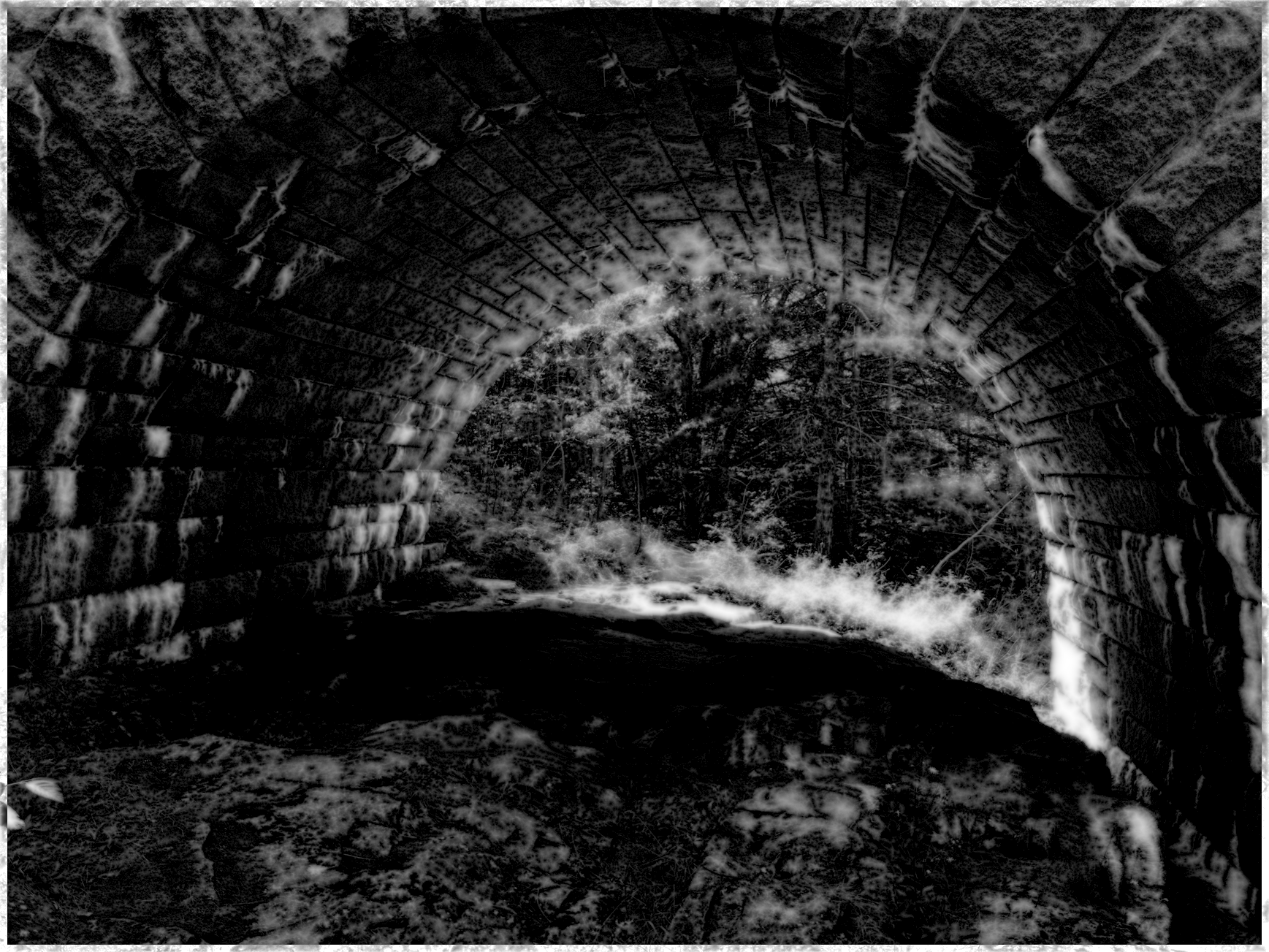

Kippy drives me back in the dark, past swooping bats and the crooning melodic croaking of frogs. Guadalupe always sang back to them “Sapo cancionero, de la noche cantas tu melancholia.” Singing frog, in the night you sing your melancholy.

I think of being five and forced into a bathroom by a girl in my class who demanded to see my penis, being ten at a Mets game at Shea Stadium and a fat old man saying to me, “Hey kid, cute ass.” when other adults were out of earshot, being twelve and the odd pitch of my babysitter’s panting as she pinned me down in a game of wrestling, being thirteen and a homeless guy following me down the street offering “I’ll suck your dick for a quarter.”, being eighteen and an older gay friend pawing me whenever he got drunk, being twenty-seven and doing a reading in Philadelphia where the hostess promised me I had a room for the night, which turned out to be her bedroom she wouldn’t let me leave when I tried. How through all of these experiences and more, I felt like I was the fucked up one because I was a guy and shouldn’t I just enjoy it?

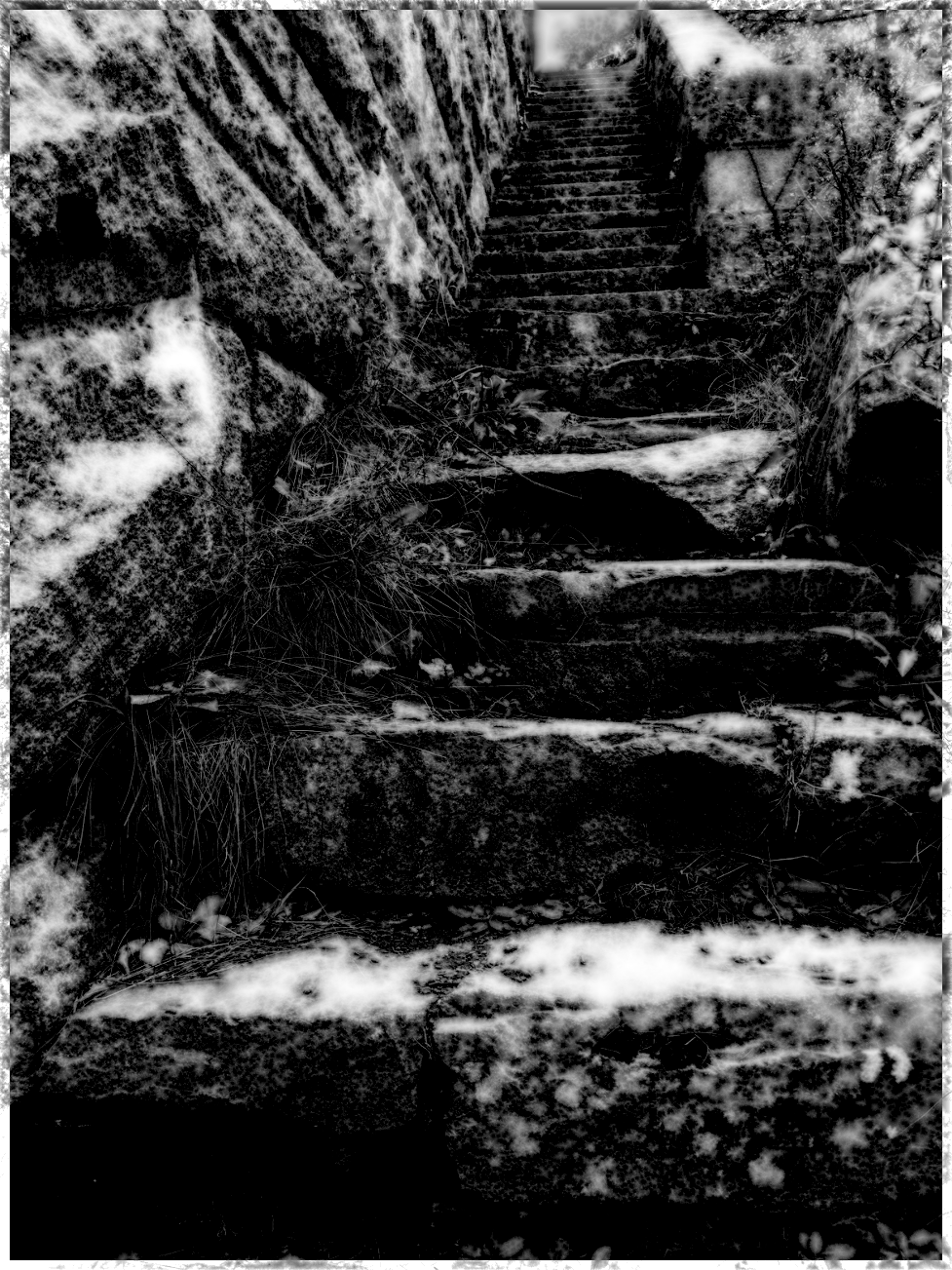

We reach the rusted black metal gate of Guadalupe’s property and Kippy keeps her brights on me as I trip up the path lined with palmeras, their fronds glowing poison green in her headlamps. I am alone in Guadalupe’s small house now.

That first night in my friend’s borrowed casita on her vast stretch of land I have nightmares I am being robbed, like I was when I lived in Bushwick, Brooklyn in my early 20’s.

Maybe it is Guadalupe’s paranoia infecting me. Before she left me on my own she warned “Pueblo chico, infierno grande.” Small town, big fire. Her house has been knocked over three times before, so maybe I am just being realistic.

I wake up to glaring sunlight, safe for the moment in my sweaty nightmare tossed sheets. I wonder how many other of the revelers from last night went home and dreamt of a world where we were violated. And if the lush beauty of the tropics will ever be enough to quell those visions.

the old systems are being destroyed

the old systems are being destroyed