In the summer of 2013, my dad convinced me that I needed an iPhone for everyday life. Previously, the mobile phone that Rich and I brought with us, if we went out of town, in one of our two 1999 Ford Econoline vans, in case we needed to call AAA, was a Trac-Fone. And you couldn’t really text with a Trac-Fone. My dad, a retired USN helicopter pilot, was an early adopter of technology. When I finished school and moved back to Mystic in the summer of 1990, he had a corded Motorola phone in his car, that was in the middle console, nestled between the drink holders. He loved to call ahead to his destination that he was “on his way”, and when he was fifteen minutes out.

The first text message between my dad and I was on 25 July 2013 at 12:07 pm:

LG: “Michelle: Running a little late: be there by 12:45 to 1. Please acknowledge. Thanks, Dad.”

MG: “Got it…that’s fine.”

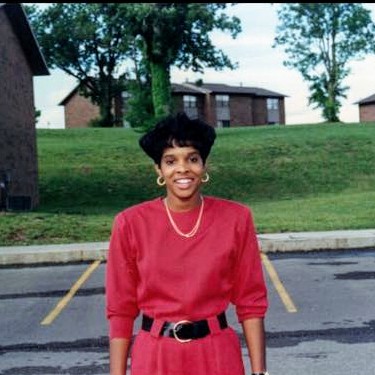

It was a Thursday, and I had been at work since 9 am at the Mystic Army Navy in Downtown Mystic. I had been co-owner with my dad of our two stores- one in Downtown Mystic, the other in the Olde Mistick Village, since September 2010, when his business partner (also his best friend from the old neighborhood), had retired after 17 years. They reached an agreement, and then my dad made me the co-owner. There was an understanding between the both of us that I would be taking over the two stores, when he was ready to retire. That day seemed far off at the time. I felt more than ready for the future change of ownership.

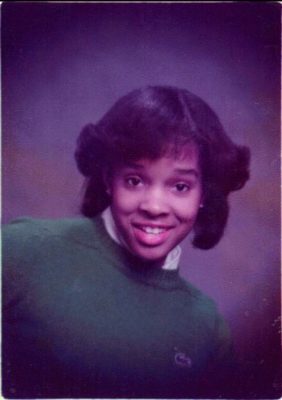

I had been raised in the family business, A Stitch in Time Boutique in Downtown Mystic, opened when I was five years old. Although we lived in Noank, my sister Maria and I would take the afternoon school bus that routed to Downtown Mystic, and we would get off at Pearl Street, and walk across the street to the store, where our mother worked the final shift that ended at 6 pm. Maria and I loved being at the store, and “helping” the customers, and would thrill to the attention that ensued: “Oh, I want the little lady to show me the silver rings in the case…” Our summers were spent at the store, working as a family. By the time I was fourteen, I was on a schedule, and have been ever since. As I was back in Mystic that summer of 1990 , I resumed working at Stitch in Time for my mom. Rich and I started our relationship then, and I found myself swept up in the excitement of an intense art scene in Mystic, that he was integral in, and I became enamored with photography. In 1995, I was fortunate to gain the employ of the professional photographer, Rollie McKenna of Stonington, until she retired in 1998. At that point, I joined the newest family business, Mystic Army Navy that my dad had started in 1993, to fill the void, post- divorce, where my mom “got the store” (Stitch in Time), and my dad “got the house” (in Noank), and “got the boat”.

I had invested in the family business. I was involved in every aspect of helping to run the retail business with my dad and his business partner on a daily basis, but mostly I was chief negotiator between the two Navy veterans, each stationed at their preferred store, my dad was at the downtown store(DT), and his partner at the Olde Mistick Village store(OMV). By the summer of 2013, the business was getting ready to celebrate its twentieth year in business, and we all felt a sense of relief, especially after surviving the tumultuous Hurricane Sandy catastrophe in October 2012, when the DT store flooded up from the floorboards as a tidal surge from Long Island Sound forged into the Mystic River. The DT store had to be emptied, and all of the merchandise relocated to the OMV store. The store had to be bleached and dehumidified, and then rebuilt, and it had been the most difficult professional experience thus far. However, our staff performed on a high level; it was all hands on deck in true Navy fashion, and we were successfully back on track.

Little did I know that three months after getting the iPhone, my father would pass away on 27 October 2013. The five day sequence leading up to his death, is burned into my memory, and I realized that this year, 2019, marks the six year anniversary, and as such, the days and dates are lined up in the exact order as they happened. I went into my iPhone for the first time to look at all of the text messages between us, which are all still there, buried at the bottom of my phone.

Prelude on Monday 21 October 2013: 12:46 pm

LG: “Michelle: Don’t forget I have an endoscopy tomorrow at the WHVA (West Haven VA) hospital. Not sure about Wed/Thurs/Fri at MANS (Mystic Army Navy Store): depends what they find? I’ll keep you posted. Love, Dad.”

MG: “The store will be fine..Don’t worry there, and try to keep the worry component down..Keep me posted tomorrow.”

Tuesday 22 October 2013:

My scheduled day off, and I had a photoshoot planned at 2 pm, with a brand new model: a veritable “Greek God” that Rich had enthused about to me, Titus Abad, who happened to be a most ardent fan of Slander, Rich’s latest band. Titus and I were going to shoot at the Greek Revival Mansion in Old Mystic, the “House of 1833”, run as a Bed and Breakfast by Evan Nickles, a longtime Mystic entrepreneur. Titus was 20, and had participated in some photo shoots at school, but had moved back to Mystic, and I was confident that we would hit it off. It was a great shoot. I didn’t text with my dad that day, but we talked on the phone. It had been a month of mostly minor physical discomfort: he thought he had an ulcer and wanted to get it checked out at the VA. He was in fair spirits, but I could tell that he was worried. He had just turned 70 on September 19th, and out of nowhere really, he seemed to taking the birthday milestone hard. He was the most vivacious person I have ever known, so to not be up on the mountain, that was so unlike him.

Wednesday 23 October 2013 at 3:52 pm

MG: “Any news on the biopsy and cat scan?”

LG: “They found one small polyp in my stomach & sent it out for biopsy. Results due in today with cat scan results. Went to see my GI (Gastro-Intestinal) guy here in New London this morning, and I’m going to let him take over the GI stuff. West Haven just too far away.. will keep you posted. Love, Dad.”

My dad loved the West Haven VA Hospital: he had a procedure there in December of 2011, unrelated to his current state, and he always raved about the legendary treatment he had received there. But Pat’s schedule with her new job, which required some serious travel, would have an impact for his future medical appointments, which is why he was considering the local doctor.

We talked on the phone a lot as I was running the two stores , while he was convalescing at his house between doctor’s appointments this week. He was still involved in daily store business, and we would discuss store banking, and other pressing matters. That night he and his girlfriend Pat went out to a scheduled dinner in Providence, and attended a theater fundraiser. They got dressed up in fancy clothes, and from the photographs I later saw, he looked fantastic on the outside, with a big smile on his face.

We’re both Red Sox fans, and that year, our team was playing in the World Series. Later that night, we texted at 9:41 pm

LG: “Cards making too many errors!!!

“Triple Play! Wow!”

MG: “We like this lead, but Sox have to realize that no lead is safe..”

LG: “Agree!”

“PAPI!!!!!!”

MG: “Love it!!”

LG: “Spectacular!!!”

MG: “Awesome!”

This back and forth between us was during Game One at Fenway Park, and the Sox won 8-1.

We were excited.

Thursday 24 October 2013 at 1:05pm

I was at work at the downtown store, and I texted my dad:

MG: “How are you feeling—it’s beautiful out there-hopefully you can catch some warm rays!”

LG: “Having lunch: back later.”

MG: “At home?”

LG: “Yes!”

Later:

MG: “How are you feeling? Any pain today?”

LG: Actually took a full Vicodin last night and slept straight through!!! First full night’s sleep in about three weeks.. Having a meal with us, or just appetizers? Thanks, Love, Dad.”

I was working until 4 pm, then had a mammogram appointment at Pequot, and Rich had a gig at the El-n-Gee later that night with Slander, and I planned to attend with my friend and model Jane, and would be meeting up with Titus there as well. But I wanted to see my dad for dinner and a visit for a couple of hours beforehand. We had veggie burgers and a bunch of appetizers, but he was not his usual self. He was down, and I know he was worried about the medical results.

Later that night, while I was at the Gee, he texted me updates on Game Two of the World Series at 8:53 pm

LG: “Top of the 3rd¨Sox finally got a MOB, but then fly out. Waca throwing much heat, but so isn’t Lackey!”

He kept me posted throughout the game, which resulted in a loss for the Red Sox (Cards 4 Sox 2), though Rich and I made it home to watch the end of the game, with the Sox down.

MG: “We’re home now, and hoping for the best!!”

LG: “Cliff-hanger!”

Friday 25 October 2013

I went to work at OMV for my regular shift of 10-6 pm. My dad normally worked with me out there every Friday, ever since his partner had retired, and we always had a full plate with receiving merchandise, and wanting to get everything in place for the always important weekend. My dad, who enjoyed a good meal immensely, always treated every Friday with a takeout lunch from Mango’s. The Garlic Cheese Bread: “Mozzarella & Romano cheeses, fresh garlic & olive oil on our hearth baked flat bread.” and The Blacksmith Salad: “Crisp lettuce, grated Romano and Parmesan cheese, mushrooms, tomato and red onion. Served with our house balsamic vinaigrette dressing.” It was easier to manage a few bites of bread and salad around customers, and making sales.

But we hadn’t ordered lunch from Mango’s since the last time we ended up working together out there, October 11th, a Friday, two weeks earlier.

So I texted him at 12:19 pm

MG: “How are you feeling today?”

LG: “Ok. Slept good again last night. The VA needs more blood work today, so Pat and I are driving to West Haven today & procedure is next Tuesday (cat scan with needle biopsy), Keep you posted. Love, Dad.”

And then he got back to me at 5:40 pm

LG: “Hell’s bells!!! Just got back from West Haven & they called & said my potassium level was dangerously high (6.5), and it should be under 5. He told me to go to an ER ASAP to get it lowered immediately! Life’s a test, Michelle & Maria, & what doesn’t kill us will make us stronger!! Love to everyone! Dad & Grandpa.”

MG: “Good Luck!! What do potassium levels indicate? Where are you going to ER?”

He was at Pequot, and I was planning on going over there to visit him right after work. When I got there, his potassium levels were already stabilizing and he seemed in fine spirits and little pain. But because Pequot closes at 10 pm nightly, and is the outpatient arm of Lawrence and Memorial Hospital, they decided to transfer him there for the night so they could monitor him. Before I left to go home, Pat went to their house so she could pack an overnight bag for her and my dad, as she planned on staying the night with him in the room. I wished him a good night and went home. The next day I had to open the downtown store at 9 am, and planned to visit him at L & M after work at 5.

26 October 2013 at 8:07 am

MG: “Good morning!”

LG: “Good morning! Fairly decent night’s sleep! Waiting for ultrasound. Can eat after that!!!”

MG: “Great! Did you text Maria last night or this morning? Let me know how the day goes..”

This was the last text message between us, as he was busy with tests and doctors in and out of his room. He called me later at work, and told me how he had talked to Maria, and his business partner, and some other friends and family, just letting them know he was getting some tests, pretty normal stuff still.

Game Three of the World Series was at 8 pm that night, and our house was Sox HQ for a few close friends, so they were planning on coming over to watch the game. I headed over to New London to go visit my dad at L & M, and would keep Rich posted. Visiting hours were over at 9 pm, but at 8:30 the doctors came in to take him down the hall for a MRI, as they were still trying to discover what was going on with him, so I said goodnight to him, and told him that I would come over with Rich on Sunday since it was on our day off. I left L & M, and had taken Exit 88 to get back home, as the van was acting up, and I didn’t want to press it on the highway longer than I had to. I was about to pass by the Dairy Queen in Poquonnock Bridge when a call from Pat came in to my iPhone, so I quickly pulled in to the DQ, and took her call. She was hysterical: the doctors just told her that he would not live through the night! The MRI had finally revealed the source of all of this: pancreatic cancer, and his organs were now in final shutdown. Stunned I told her that I was on my way back to the hospital. I sat there, and called Rich in disbelief, and told him that I would be in touch.

We sat in his room and I held his hand and talked about the store, and happy times, sailing on the Mystic River into Fishers Island Sound, and so many others. I told him that I had anticipated taking the store over when he was ready to retire, and not that he would be throwing the reins to me! He laughed.. Pat dialed the number of every family member and he talked to them, so bravely and lovingly. Then she dialed the number of all of his Navy buddies and I could hear them breaking down in shock and he comforted them. I talked to Maria in Syracuse and they were having an early Autumn snow storm, and since it was her oldest daughter’s 12th birthday the following day, she had 8 girls at her house in a sleepover party for Emma. My dad recorded a birthday message for Emma that night in his hospital bed, and I don’t know if she has ever heard it. But I urged Maria not to drive down, as I felt it was too dangerous to risk. She was having a hard time with it, and she really wanted to come down. By midnight they were upping the morphine, and he was trying to rest and sleep. Pat was in his room and the rest of us were out in the waiting room. I left at 6 am, and everyone there was trying to doze. I went home and sat there.

Sunday 27 October 2013

Pat texted me at 9 am that he had passed. With Rich by my side, I called Maria, my mom, and Gordon at the store so he could tell the rest of the staff.

The very last text message entry from his contact in my phone was from Pat using his phone because she couldn’t find her phone and we were making funeral arrangements:

PB on LG’s phone: “Heading back home to find phone.”

MG: “I am at Dinoto in the parking lot drinking coffee. I will wait in my car so I can help you carry the photos in when you get here..”

______

Thank you to Rich for the title, given to me five years ago on the first anniversary of my dad’s passing, and all I could do was to schedule another photo shoot with Titus on 22 October, a tradition we managed to uphold until recently, thank you to Titus!

Thank you to Red Sox HQ: Peter Jazz, Humpy and Malthus!

Thank you to Dan Curland, who almost died the same night as my dad, having choked on chicken at dinner, and saved by his daughter Lena running to our house down the street and getting Rich and Peter to go help him. Dan was brought to L & M the same night that my dad was there, and turning the corner, I bumped into Peter Jazz!