Suddenly, in the last week of August of 1995, I needed a new job. I had been raised in the family business in Downtown Mystic, A Stitch In Time Boutique, and had acquired a fledging interest in fine art photography through a young roster of poets and musicians in my hometown. I was introduced to a new Rock and Roll family now, and I had made significant forays into local exhibitions and publications, and had set up my own darkroom in our rented artist collective in Stonington. In fact, it was a fellow artist in our homegrown art scene that told me that Rollie McKenna lived in town, and she was an important literary photographer, having photographed the likes of Sylvia Plath, Dylan Thomas, and many others. Albert was always incredulous as he stated, “and she lives right here in Stonington!” So, on August 31, 1995, I took the phonebook out, paged to the listings for “M”, and found “McKenna, R” in Stonington, Connecticut at 1 Hancox Street, and I dialed her number. She answered the phone, and I introduced myself as a photographer who was looking for a job, “did she need anybody right now?” She said, “As a matter of fact…I need someone to do some research for me, as I’m working on another book.” I answered promptly that I could help her out, so she suggested that I come to her house the next day so we could meet in person.

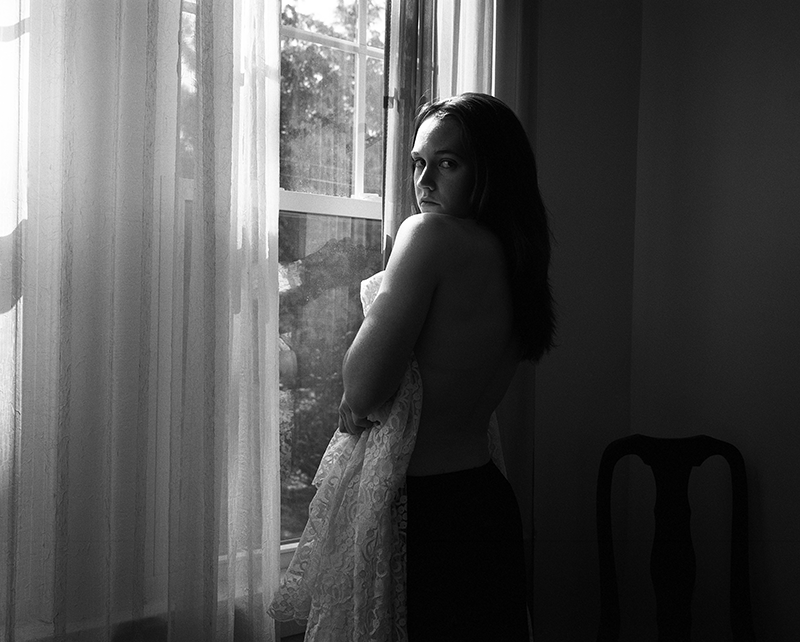

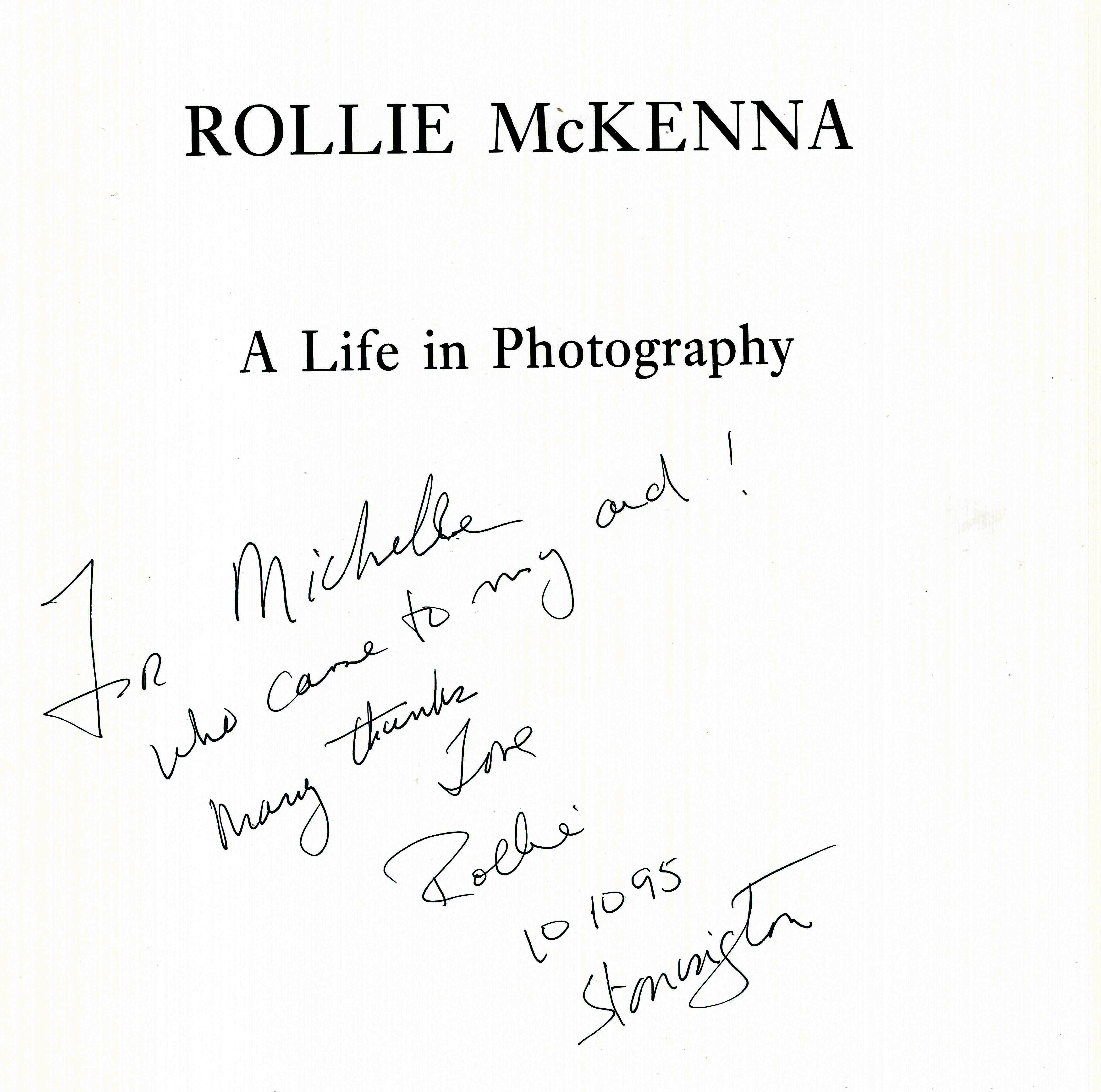

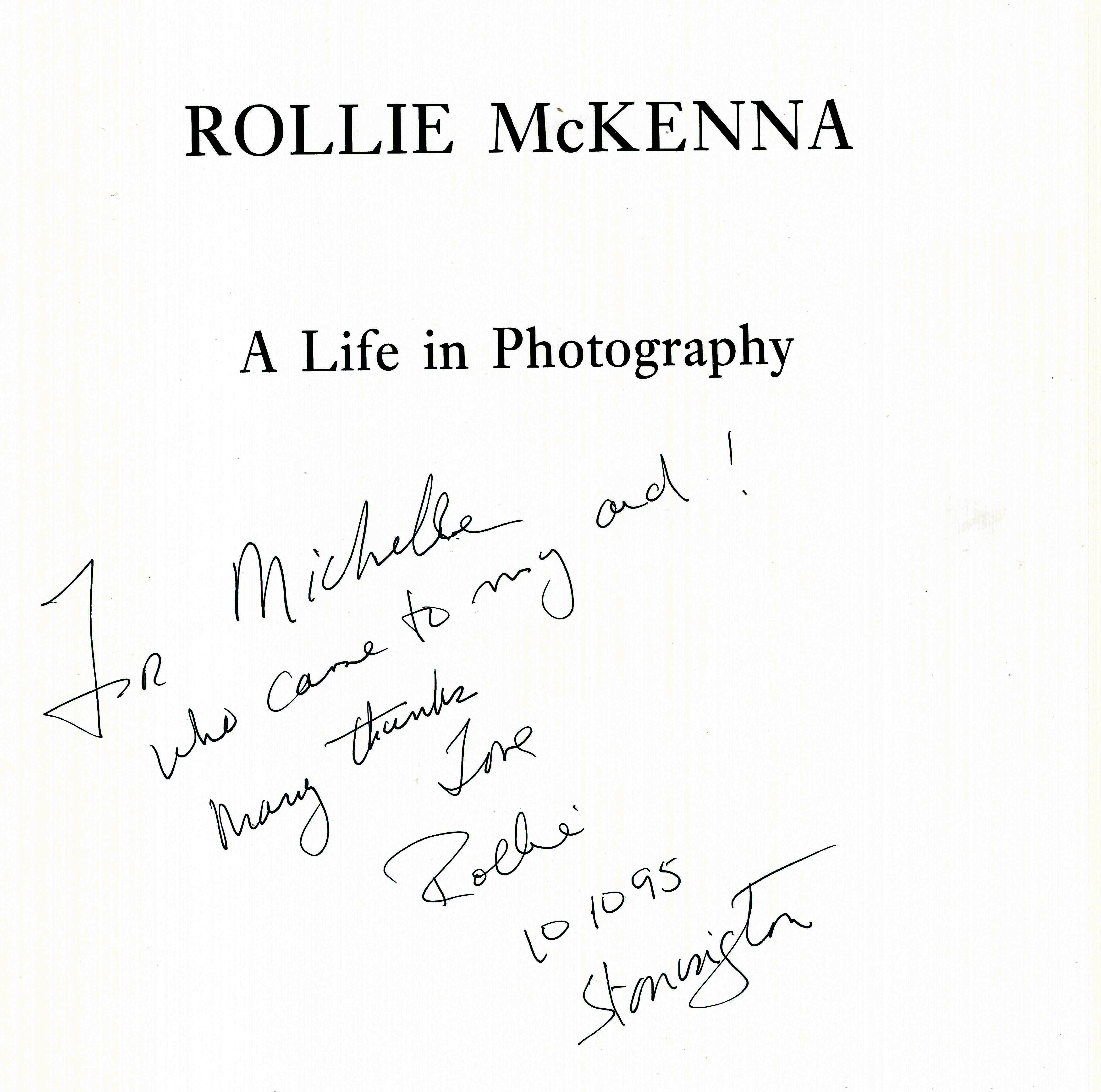

We sat on the back patio overlooking Sandy Point, and discussed her new project. She had published her autobiography, A Life in Photography (Knopf 1991), and in 1995, she was looking to complete a visual timeline of the many poets and writers that she had photographed in the 1950s through the 1980s. The new book would feature each writer with an older photograph, next to a brand new photograph, along with a short biography of each writer that I was being hired to write, and a piece of “new“ work, by each writer, that Rollie called a “gleaning”. I clearly had the easiest job, as it would prove challenging to get some of the writers to sit for a new photo, and produce new work. The time that had elapsed between each earlier portrait and also their literary output was the overriding factor. The photographs captured the vanity and vulnerability of her subjects. But she was fearless in her vision, and she parlayed that same enthusiasm to me on the first day in her studio, which was September 5th, 1995 at 145 Water Street.

She handed me a copy of her master list, “People Photographed as of September 1995”, a nine paged single spaced alphabetical listing of the artists in her photography archives. We fully reviewed the list together, and started updating the dates of her most recent shoots. I immediately began a handwritten studio log, noting the date in the upper right hand corner and “Gemma and McKenna” below it, which I carefully updated each day with all of Rollie’s directions: tasks at hand, current status updates, and reminders for the next day and week. On my first day, I noted: “Searched for the folder on Elizabeth Bishop to no avail, which contains the missing third page of a letter from 10 May 1956. Need for the completion of Bishop in book, need other comments on life, other than the “lonely poet” symbol most publicly known.” I had no reference for this bullet point listing, yet I wrote it, and it would come in handy during my days doing research at the local libraries. Another note from 20 September 1995: “Pull negative of Alastair Reid from Master File (1960) and tell L and V (her photo lab in NYC) to lighten up contrast of his suit and into the background. AR8.60B #25 need two sets 5” x7” with white borders”. I quickly realized her archival system was masterful. AR8.60B was “Alastair Reid August 1960 Second Roll”.

Rollie left for Key West that October 1995 through April 1996, and we talked on the phone daily and faxed furiously. Also, letters were sent, and sometimes copies of faxes and letters that she received in Key West, like when she mailed me a copy of the letter she received from Tom Wolfe, expressing dismay at his tardiness in response to Rollie’s request for a gleaning. Every day I was working on the research for the biographies for the book. I collected magazine articles: The Sewanee Review Autumn 1972 to garner literary reviews on Rollie’s subjects, John Malcolm Brinnin, Lucille Clifton, Philip Caputo, and James Dickey. The Saturday Review 17 November 1955 for an article on a review of Dylan Thomas in America: An Intimate Journal, by John Malcolm Brinnin , by Louis Untermeyer. Mind you, this was all before the Internet. I could not Google ”Philip Caputo”. I also dove into Rollie’s sizeable and extremely well organized photo archives. To this day, 23 years later, I have enacted many of Rollie’s organizational techniques. It was of utmost importance to be able to manually retrieve any photo at a moment’s notice. Judith Bachmann handled the affairs at Rollie’s house, each day fielding phone calls from literary agents looking to gain clearance for publishing one of Rollie’s photographs.

At first, requests for a new print would go to Rollie’s photography darkroom of choice, L and V Photo Lab in NYC. We would carefully pack up rolls of film, and negatives and overnight them to the urban studio. But then I suggested that I could get Rollie’s darkroom at the Water Street Studio back up and running, and that I could handle all of the darkroom printing. By early summer of 1996, Rollie got a call from the Muskegon Museum of Art, in Michigan. We had sent them a copy of her autobiography on my second day of work back in September of 1995, and the Museum had finished selecting the 61 images from the book that they wanted for a Rollie McKenna solo exhibition. I inventoried all of Rollie’s framed photographs boxed up in the studio, and made a list on 31 May 1996, that we had 37 framed photos, ready to go, and 7 to be framed, and 17 to be printed and framed. I got busy right away printing up those 17 photographs, as Rollie was due back from Key West on 10 June 1996, and the moving company was booked to transport the exhibit to Muskegon on 26 July 1996. I finished printing the photographs, then sent the photos to Studio 33 in the Boro, to be matted. In the interim, I ordered all of the framing hardware, and a small party of us assembled and framed the remaining photographs at Rollie’s studio. Then everything had to be carefully labelled and packed up.

Rollie announced to me that the Museum wanted her to give a speech along with a slide show. She said that she wasn’t up to organizing the slide show, and writing a speech; remember that in 1996, she was already 78 years old: an extremely hardworking and passionate artist, but still, she had to contend with some heart issues from time to time and a milder case of forgetfulness. So I jumped on it. I culled the 36 images for the slide show, and found that over half of them needed to be produced into slide form, my first experience shooting slide film with a light set-up. My notes from Rollie said that “a blue tint suggests the wrong filter, and that I should use TMAX 100 film with a ASA of 50, and to make sure that the image on the copystand was equidistant to the lights”. These tips would come into play for me when I later worked for the Stonington Historical Society after Rollie moved to Northampton in 1998.

After the slide production, I settled into writing the speech from Rollie’s perspective, so that she could read my text, transposed onto index cards for easy reference. On the Denise Levertov slide from 1969, I wrote, “I approached Denise for this photograph again to join the legions contained within the Modern Poets, Second Edition (McGraw Hill 1963). She made the peculiar demand in her response, ‘She wanted the right to have destroyed the negatives of any photographs I wouldn’t like to have in circulation….’ I said I would have to ask Elizabeth Bishop first……” Rollie said the speech and slide show was a huge success and that she was very thankful for all of my hard work.

That Winter of 1996 saw more research for the book, and completing any studio and darkroom requests. When Rollie returned from Key West in the Spring of 1997, she had a new companion who favored seclusion and privacy , and her work crew would soon find Rollie cut off from the familiar foundations. Soon everything was for sale, and we had to pack up the house and studio, as Rollie was moving to Northampton, Massachusetts. I remember her telling me that she wanted her life’s work to go to the New York Public Library, because that’s where her friend, James Merrill’s work was archived. One day when I was packing up at the studio, Mary Thacher, the then Director of the Stonington Historical Society came by, as a friend of Rollie’s to inquire what was going on, and she hired me for the Stonington Historical Society to be a photo archivist.

We wouldn’t hear anything more about Rollie until we saw the obituary in the New York Times in June 2003. Alas, her third book, to be called Poets and Writers of an Age would never get published.

—Michelle Gemma

Mystic, Connecticut

2 August 2018

Inscription by Rollie McKenna inside her autobiography “A Life In Photography” (Knopf 1991), given to me on my birthday 10 October 1995.

—-This memoir was written 2 August 2018 for inclusion in a book about Rollie McKenna, published by the Stonington Historical Society on 1 November 2018.

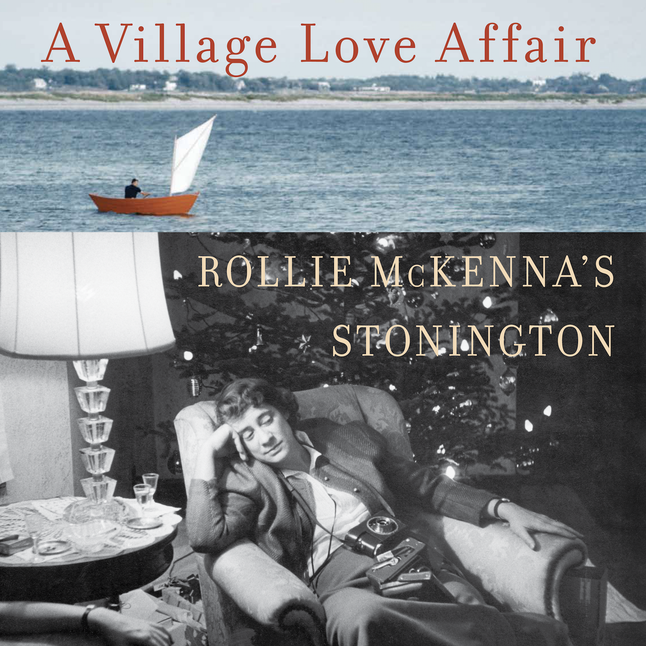

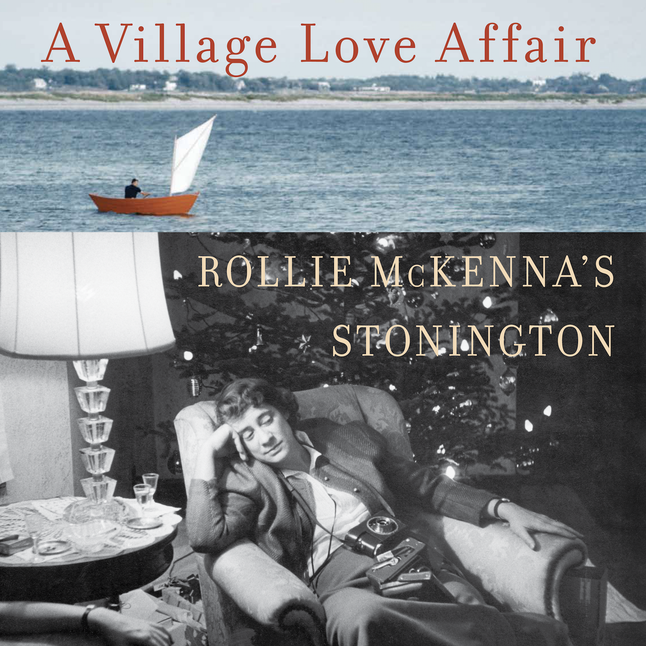

Rollie McKenna

Book cover design by Chip Kidd.