Recently, writer Royal Young suffered the loss of his grandfather, Zayde. As he writes in Fameshark, his memoir noir (Heliotrope Books 2013), “My maternal grandparents Babbi and Zayde supported everything that had to do with the arts. Their three-story house in Great Neck, Long Island was crammed with Zayde’s impressionist paintings and Babbis’ sculptures.” Royal called it “Jewish Grey Gardens”, and everything about this picture was in direct contrast to my own maternal grandparents.

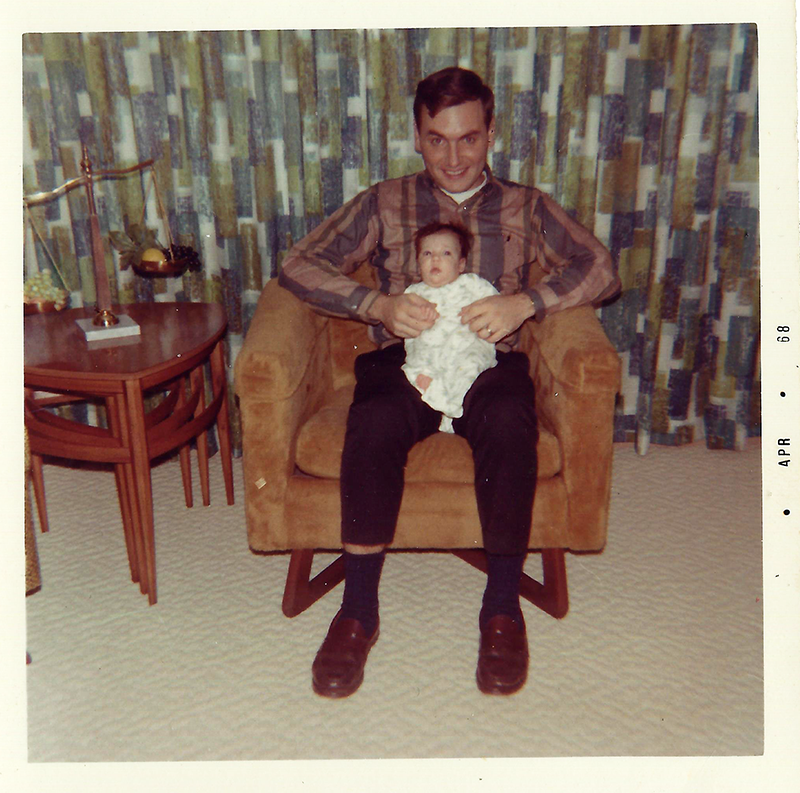

This month marks the tenth anniversary of my grandfather’s death, and I feel nothing, really. We were not close since twenty years prior, though close is a stretch to define our relationship even at all. Anthony Beaudry, my aloof French-Canadian grandfather: he smoked cigars incessantly, my father hated cigars. Whenever my grandparents came down from Worcester, Massachusetts, to visit us at my childhood home in Noank, Connecticut, Anthony was forced outside to smoke his smelly cigars. Yet the house reeked all weekend and even after they left. My other three grandparents, Anthony’s wife Louise Caputo, my paternal grandmother, Helen Pelosi, and my namesake paternal grandfather Rocco Gemma, all radiated an Italian warmth, or at least parlayed easy company.

I left the United States on January 4, 1989 to study abroad for my last college semester, meaning I would graduate while in Grenoble, France, and I had no intention of returning home for an anonymous graduation at UCONN. Plus, my parents’ divorce was finalized on August 17, 1989, a process that started in the spring of 1987 when my sister was just about to graduate from high school. Time was up, and my mom made the announcement, as soon as I got settled in my first dorm room, fourth semester, up at UCONN Storrs. I had just moved out of the house in Noank, after living at home for my first three semesters at UCONN Avery Point.

My sister had started college in the fall of 1987 at URI, and seeking sisterly solace would drive Route 138 West over to UCONN most every weekend, not wanting to go home to Noank. My parents had separated, but due to each of them not wanting to grant the space to the other, they were still living at the same address: my childhood home, a raised split-level ranch, where my mom lived in the upstairs, and my dad lived in the downstairs- a situation that was not fun for anyone. It took another year before my mom moved out, in the fall of 1988.

I was ready to move off campus as well, three semesters of dorm living were three too many for me. In the same fall of 1988 that my mom moved to a temporary place in her hometown of Worcester, Massachusetts, I moved into a modest Colonial brick house with four other roommates that I had casually met in the last year, three boys from Fairfield County and the sweetest hippie girl from Norwich. My sister Maria continued to visit me at UCONN, arriving at the brick house most every weekend. When I left for France in January 1989 for my eighth and final college semester, Maria transferred from URI to Northeastern in Boston, and looked up one of my former brick house roommates, who had already transferred to UMASS Boston. She moved in with him, as a familiar counterpart. During the year that I was abroad, their friendship deepened from the platonic to the romantic. When I returned at the end of 1989, it was official that they were an item.

The first family function in Worcester that spring of 1990 was a cousin’s school graduation, and my sister and her boyfriend planned on driving down from Boston to attend. My maternal grandfather, Anthony Beaudry, announced that he would boycott the family event, if Maria and her boyfriend made an appearance. They were living in sin, according to my grandfather. I remember being shocked that he was actually taking a stand on this distinction. He had, heretofore, never crystallized an official definition of his Catholicism. I felt that I was already growing apart from the totality of family gatherings in Worcester, having been raised in Noank since I was five, and I was at that point, barely attending the annual Christmas Eve dinners. My parents’ divorce had far-flung all previously engaged in rituals, so it was basically a free-for-all for my sister and I. We were already feeling the guilt trip that each parent passively placed on us to divide our time evenly, while visiting each side of the family in Worcester for Christmas Eve: the only relief was that at least the host of each family gathering was conveniently located just a few miles apart from each other. We tried to make it a party and have fun ourselves, but there was never a moment that we didn’t feel some guilt, if we had inadvertently let the moment escape at one house, we knew that disappointment would follow at the next stop.

But, my grandfather’s stand clearly required a response. I wrote him a letter, urging him to reconsider his position; that times had changed, and modern relationships were strengthened with cohabitation. That as a couple had the chance to live with one another, they could discover if their relationship would survive in the long run. As children of divorce, we most wanted to not get divorced. We watched our grandparents, in what we interpreted as loveless marriages: separate bedrooms, which seemed frightening, and each grandfather barking orders to each grandmother, who waited on him “hand and foot”, because… he… worked…all… day. Then we watched our parents get divorced. This is not what we wanted.

Anthony Beaudry would not budge, in typical stubborn stance. He wrote back to me, claiming ownership to his religious principles, which forced him to be inflexible in his points of view. I was disappointed, and other relatives intervened on my sister’s behalf, and life moved on. In the summer of 1990, I was not only back from Europe, I was back from an ill-fated trip out west in the US which resulted in a ski-trip accident in Vail, Colorado, and then knee surgery and physical therapy back east. I started a relationship back in Mystic, with an old friend from junior high school. As late summer faded into the autumn, I was ready to get my own place in Mystic, and found a lovely apartment located within the glory of a local mansion, run by my friend Courtney’s family. My boyfriend Rich moved in with me that October 1st, just two short months after we started dating. I was now living in sin.

As my sister and I were the two oldest cousins out of the eleven that comprised my mom’s side of the family, we were the first to experience the many rites of passage throughout our childhood. It makes sense that we would be the first to break ground in the family with boyfriends and living arrangements. As Grandpa Beaudry aged, it seemed to matter less to him, when my younger cousins experienced the exact same milestones, and they moved in with their significant others. My mother was always bitter about this. As well, my grandfather had tried to convince my mom against getting a divorce, on religious grounds, but he lost that argument. He, however, in a finely tuned maneuver, never acknowledged my mom’s new partner that she was living with in Mystic. My mom visited her parents solo from 1992 until her parents’ death in 2009, just ten months apart from each other: January 3rd and October 3rd, 2009.

I could never grasp religion with my grandfather’s type of dissociative fervor. In my childhood, I resented being brought to church weekly, and worse, being forced to attend “Sunday School” at the local high school, adjacent to my church, which was across from the town police station. I could not buy the basic premise of Catholicism, that the Pope was infallible. Noone was infallible. It did not make sense to me. I dreaded church and stopped going just after my confirmation. I understand the structure that religion provides for the ceremonies of life- baptism and marriage, and for the ceremony of death.

Placing judgment on life itself: to define “living in sin” did not have merit to me. The years passed quietly from 1989 to 2009 for me in my relationship with my grandfather. I was polite, dutiful in the sense, that I would not embarrass my mother. I even conceded a visit to him in the nursing home, when all that was keeping him alive was a feeding tube. His mind was gone, and his body followed on the third of January, 2009.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-1382040-1214776997.jpeg.jpg)