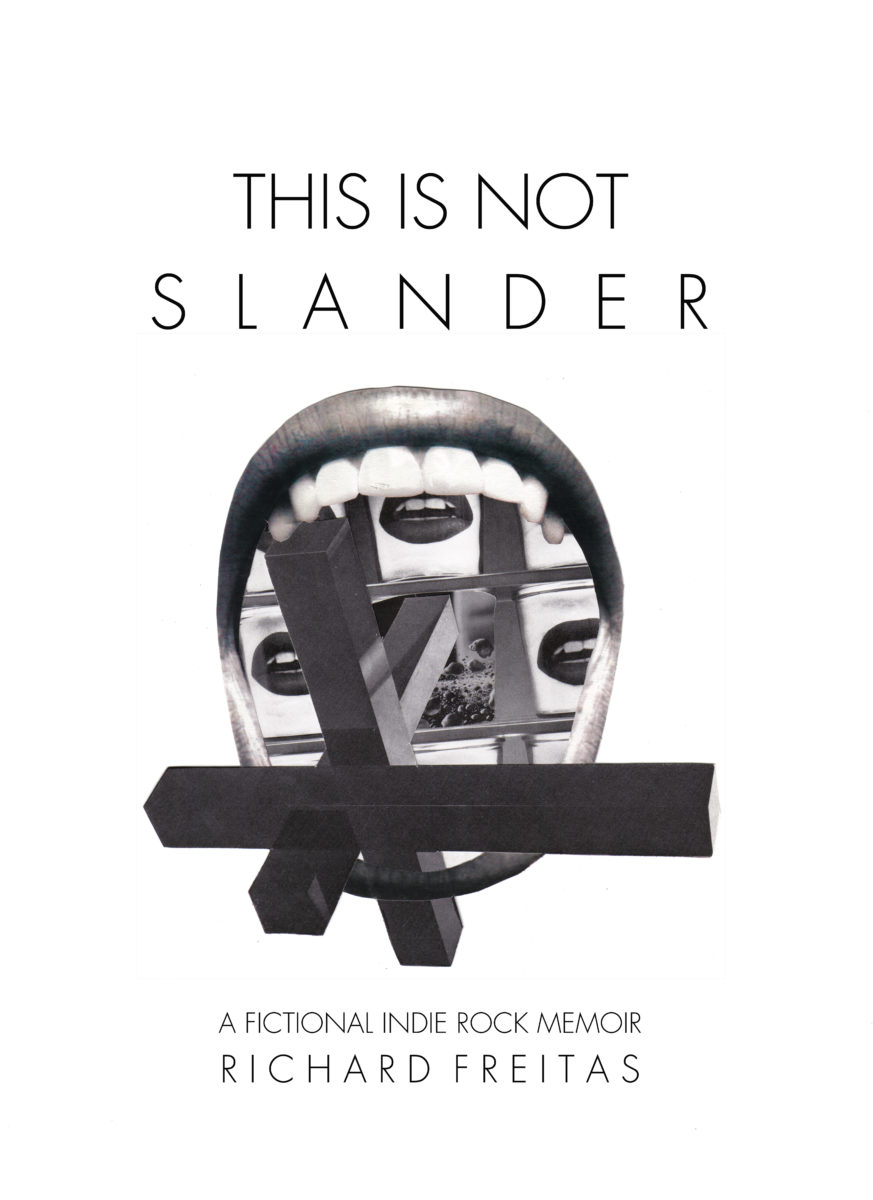

A FICTIONAL INDIE ROCK MEMOIR

It’s getting harder to deal with the blood in the toilet.

I had always subscribed to the notion that I would succumb to a stroke, as my father, and each of my four grandparents had. Perhaps this is the totality of my chosen lifestyle; a detriment to all concerned. I fear I am rotting from the inside, repeating the same mistake I vowed not to. Succumbing to a stroke was the main tenet of my mortality- that thought was something I always could depend upon; like holidays, or capitulation. The lesson from the experience of coming out of “retirement” and joining an active rock band at age 43, and playing drums with Piercing, has been that you never know.

You never know what is going to happen. My health could be due to stress from the band, or perhaps the larger context in which the band contributes toward it- the rescheduling, the negotiating, the cajoling, the convincing: The reinforcement of a belief system. I’ve been doing the work of four people for two years now; drummer, manager, roadie, publicist. Perhaps my body is rebelling against the demands I have placed on it. Hopefully, it won’t take long to find out; I have never before felt my musical life would threaten my actual life.

Jocelyn emailed me, a random inquiry I was not expecting, asking me to play drums in her new band. At that point in my musical life, she was the only person I would even consider coming out of retirement for, but I was shocked at first. Jeremy, a mutual friend and regular at the Record Palace- our local record store where he was a regular and I worked, had regaled me about her disappointment in the studio project Borealis, which Jocelyn had participated in with a coterie of musicians- creating songs at random, in a total studio setting. Steven Giles, Malthus Prufrock, and I had spent half a decade- from 2006 until 2011, deep in the studio, crafting two full-length albums and four singles as Borealis, and Jocelyn had sung on roughly half of those songs. Steven, Malthus, and I had been friends since meeting in 1985, as high school students with an inherent and sincere love of music.

Jeremy loved to tell me about Jocelyn’s reservations about the Borealis material, mostly the production.

“She doesn’t even like it, you never built the reverb bed she was striving for…” he would say, reveling in my frustration, as we felt the songs, and the production, were spot on. I couldn’t understand his motives in revealing this information to me. Was he jealous of Jocelyn having the opportunity to appear on the Borealis material? And why did I not hear these criticisms directly from her? And yet, I had trouble reconciling within myself why it would matter what he said, or what she told her friends who were not involved. Was I being possessive? Did I subconsciously view Jeremy as a threat? A threat to what? I had given up on a career in music, but by returning to the fray as the drummer in Jocelyn’s new band, was that feeling to be exposed?

I first met Jocelyn when she, Jeremy, and Todd arrived at my demo studio in 2005 to record their teenage band The Infectious Reality. Jeremy and Todd were local Mystic kids of the next generation of musicians from town, a tradition that had gone back twenty years by the time they started their first band. While becoming regulars at The Record Palace, they would spend hours there, buying all of the correct albums of the time, such as Broken Social Scene, Daft Punk, and Outkast. They also were privileged to be a part of the extended Palace world, which exposed them to the timeless catalog- Byrds, Dr. John, Joni Mitchell, Spirit, Primal Scream, and Augustus Pablo. I had been working at the Palace for eleven years when the two of them first showed up to haunt the bins.

The Palace was one of the last great record stores; one of the few that survived the transition from the analog world to the digital world. A great portion of the store’s survival was due to owner Benno Bluhm liquidating his entire savings and retirement, as well as selling his house,to keep the store afloat during the Great Recession. In addition, there was his clientele’s fierce loyalty to the tiny 600 foot store, it’s walls covered in a collage of promo posters, autographs, and local memorabilia- located at the very heart of Mystic. The Palace was the only place I knew of where you could buy a used copy of the Carole King LP your mother used to serenade you to sleep with in the seventies, see actual tickets from the Woodstock Festival which Benno attended, as well as albums signed by the Beastie Boys, guitars signed by Blink-182, or the ubiquitous Graham Nash autograph, who was a close friend of Benno, following Graham’s first visit to the store, in 1989. In this small town, The Palace was a unique treasure.

One afternoon, Jeremy and Todd asked me to record their new band, and I immediately agreed; secretly thrilled that there might be new music born in the town. The entire philosophy surrounding my musical career was to put our hometown on the musical map. As someone who watched plenty of talented musicians leave town for the more fertile ground of NYC, which was a short two and a half hour drive from Mystic, I found a direction as a young musician that arriving at “success” would be far more meaningful if it was accomplished here. I had spent the past twenty years playing in bands, playing in side projects, producing demos, setting up shows and curating festivals. In addition, my extended group of musician friends ran a collective rehearsal space for five years, hosting various musical acts for practice space, and darkroom services for photographers. We also organized underground raves to help offset a sudden $700 heat bill in January, or any other financial issues. And, of course, the DJ’s were all members of the Collective.

The talent of The Infectious Reality hooked me immediately. Once Jocelyn stepped into the studio, that night of our first recording session, I knew she was a star, or at least I had the overwhelming feeling that she could be. She carried herself with a graceful insouciance beyond her years. But what really attracted me to the project of recording their first demo, was the quality and breadth of their music; and Jocelyn’s singular voice. The Infectious Reality had a sound which was perfectly retro; a groove driven punk rock aesthetic, with searing dual vocals unheard from such young musicians, while simultaneously lacking derivation. It was a tall task on a canvas that had been almost completely filled, and for a pair of fourteen year old kids, with a 16 year old singer, it seemed that their possibilities were endless. They wrote the basis of their songs on an outdated Casio sequencer, and yet both Todd and Jeremy could sing, play bass, guitar, and keyboards. In all of my years of making music, and striving to get traction in the music world, here were three kids who I thought represented a better chance of making it than any of the previous groups in town.

The Infectious Reality recorded two four song EP’s at my humble demo studio, which I dubbed Centraal Studios, in a nod to the Amsterdam train station. I had been to Amsterdam twice on the recommendation of Benno, and found the train station so immense, it was a perfect opposite of my studio. The room was twenty-two feet by twelve feet, and every inch was filled with recording equipment, drums, guitars and amps, as well as my turntables and mixer. And the kids loved working at Centraal, so different than their own or friends bedroom studios,with parents listening down the hall.

After completing their first EP, they hawked their home recorded CDR’s, with Xerox cover art I had designed, in the halls of their high school, and at their shows. The cover image was an ancient abacus with an electrical cord photoshopped onto the left side of the first analog computer. They believed in the analog / digital contrast of the cover design, as they were musically mixing live guitars over drum machine programs. I explained exactly how they could go about selling it to their school peers, as the members of Thames utilized the exact same strategy when we released our first home recording. The Thames EP was on cassette tape, which was the only available medium at the time. The Infectious Reality sold their record on CDR- “Digital Cassettes…” said Jeremy.

“Ok, during breaks between classes, find the busiest hallway, and offer the record for a plain five dollars.” I explained “and what makes you think you know the busiest hallway when you haven’t been there in almost twenty years?” sarcastically offered Jeremy.

“I don’t think he means the same fucking hallway as in 1987 ya punk….” Offers Todd in a slow drawl, at once to poke at Jeremy and to let me off the hook. “Look, it’s easy. Have you ever been offered to buy a local bands CD in the hallway at school?”

“No.” they respond in unison.

“That’s the hook. And people want to be around people who are getting things done, making things themselves.”

“See and be seen.” Jeremy restates an axiom from the Greenman Collective days that I have weaned them on since I first felt they were worth the investment of my energy and the Post Generation ethos.

“Get the grinder and eat it.” offers Todd.

“Point of completion.” I add as a final statement, as if we were fighters pointing our swords toward a central point.

We agreed the finances of the group, which I meticulously accounted for, (having been part of many monetary mishaps within a working band) would not discount their voices. After six months of selling their first EP, they were able to buy their own PA and began to see a return on investment in real time. Invigorated, they recorded their second EP- distributed it in exactly the same way, and built a considerable local audience within the all-ages set. For the most part, everything was going according to the plan- there was a great working relationship between the four of us, and yet Jeremy and I held a more intimate bond, as he began to work at the Palace, and was constantly honing his depth of knowledge through countless hours of listening and conversation.

“Did you know Radiohead is named after a Talkingheads song?” offers Jeremy in the cool silence of an early summer Friday morning at the Palace. The heat at the Palace could become unbearable as the day went on; the sun clearing the roofline of the building around 1 PM.

“Wait, what?!?” I offer somewhat shocked. I was a huge Talkingheads fan, I chose their song “The Great Curve” as the submission for my Music Listening 101 exam as a high school sophomore.

“Yeah, side two of True Stories.”

I head over to the Talkingheads bin about ten feet in front of the counter. Sure enough- a copy of “True Stories” is there; it’s minimal yet garish design so evident. I flip over the jacket, scanning the song titles. Track two on the second side. The kid was paying attention to the details.

The Infectious Reality eventually got a big break, an opening slot in New Haven- their first out of town show. I volunteered to drive them down in my conversion van; a pretty nice ride for your first excursion beyond the city limits. They acted like young professionals, each of them dressing it up in an appropriate manner- Jocelyn especially shined in a purple dress with satin regality. They certainly presented themselves as wise beyond their years, but the music would have to back it up. And it did. Slashing guitar lines, pristine harmonies, and a smooth transition between songs, with no amateur fumbling.

They performed to the height of their capabilities, and after the set, the headliners, a New York City band of mid-twenties guitar slingers couldn’t heap enough praise on them.

“You guys are just teenagers? That show was fantastic! You should definitely keep it going and we could probably hook you up with shows in the city.”

Unfortunately, their set at The Free Frame of Reference in New Haven would be the final Infectious Reality performance.

I had known Steven for twenty years when we both found ourselves, for the very first time, without a live working rock band as part of our daily routine. We met in high school in 1985, when he was a junior while I was a sophomore. For the next nine years, the two of us, with Brent Davis and Thomas Field, would play music as Thames until 1994- our ungainly end included a $20,000 debt. Steven had recently built a studio in his house, a transition solely made toward recording over assembling a live act. It was the smart move; as the internet was becoming the new record label, and as such, you could now reach a possible wide audience without ever packing the van or risking a finger being smashed in a closing door an hour before the show. As much as Steven and I had worked together in the past as members of Thames- sharing a vast musical dialogue- adding Malthus was the easiest answer to a way forward. While Steven was building the studio, he put in an incredible amount of time to learn the new technology, but Malthus was already a tech genius. He and I had lived together for a few years in the early 90’s, and I’ll never forget one particular night when he called me downstairs to his room.

“Hey man- you have to check this out.”

On his desk was a phone receiver sitting on a small plate with two recessions to let the phone settle into its framework. I immediately recognized the “plate” from “War Games”; one of the seminal 80’s movies we had all seen a hundred times. Malthus was the first person I knew who was on the internet.

Steven had recruited me by promising that I would not be involved in the project only as a drummer- after twenty three years of being told to “sit down, shut up, and play the drums.” My evolution as a drummer followed a somewhat predictable arc. In the early days of Thames I was a spastic bundle of energy, desperately seeking the attention of the audience above what the band was attracting. I even came up with beats for two early songs where I stood up and played the drum set more like a marching band drummer, so I could stand on stage like everyone else in the group. Years later I realized it was another attempt at attention, although the beats actually worked perfectly within the framework of those songs. If they didn’t, Steven and Thomas would have let me know about it. I was able to eventually settle down into the role of the drummer, and once I made that adjustment, Thames truly took off.

I was looking forward to exploring, within the structure of Borealis, what I was actually capable of musically, without having to replicate the song for a live performance. It took quite a long time to actually get to that point, as at the very first session to record raw material to the computer, with designs to later cull and splice the best indeterminate moments, I was sitting behind a mic’d up drum set in Steven’s new studio. As it had always been between the two of us, once we began to play together, I could sense exactly where he was going melodically, structurally, and where the arrangement was headed. Within the first hour we had written enough material for the very first song we would complete; a driving off beat stomper that had more in common with music from our teens than what we had initially set out to do in this project. And the song was incredible. It was exhilarating to feel the grab of youth again, because of the upbeat tempo and pulsing beat. And yet, it was our maturity that was the most intoxicating element of the session. It seemed we had become adults who possessed the tenacity of youth through our ability to make music.

A week later, Malthus and I showed up for the second session, and Steven had arranged an entire four minute song from the various takes of the previous week. He had created an incredible pop number with rock flourishes none of us had used in our respective previous musical endeavors. We were stunned at the accuracy of the intention, and immediately decided to work for 4 more weeks cutting tracks from live guitar and drum sessions until we had an album’s worth of material.

A month later, after volunteering for an arduous schedule, the three of us felt comfortable that we had a full album. We had to be meticulous and get inside the songs in a way only a recording project allows, as there were no live ramifications. The liberation was palpable. We faithfully worked twice a week, honing the initial ideas with added layers of programming, keyboards, and the singular vocals of Malthus. The majority of the tunes were being realized within three working elements: rough, guitar driven rock songs, slinky electro grooves, and a minimalist blend of live guitar and sequencers. But there was one scintillating number we couldn’t get our heads around. “Out at Home” was an ambient song which was built around the application of a trip hop beat, yet was an expansive piece that demanded the listeners attention. While struggling to find its place among the other songs, it dawned on me that Jocelyn would be the perfect vocal fit. “Do you think she’ll be up for it?” asked Steven. I felt confident that she would, but there was no sense in making promises at this stage.

Jocelyn arrived ten minutes late, which I thought was a sign of confidence for her first serious recording session in something more than my little demo studio where I had recorded the two The Infectious Reality releases. Malthus and Steven had heard all of her recorded material, and seemed to be supporting me in my decision to bring a 19 year old into the fold. My initial sense was that Jocelyn would have no trouble finding her place in the working environment- she displayed a secure sense of her abilities, and never seemed to shy away from getting the actual work done. As she entered the front room and we rose to greet her, there was a palpable sense of disbelief- how could this slender reed of a person exhibit such a soulful, powerful voice? Since I had worked with her before, this was of no surprise to me. And yet, Malthus and Steven were speechless; I actually had to prompt them to get past their initial shock. This wouldn’t be the last time a producer or engineer would be taken aback seeing Jocelyn in person for the first time.

Steven had prepared the studio before we arrived, one of his incessant traits while recording; a possession that was so much of the attraction for both Malthus and myself. The four of us listened to the song a handful of times, discussing the peaks and valleys, and what we thought would work vocally. With some slight trepidation, Jocelyn stepped to the mic in the faceless basement. I stepped into the opposite half of the room with Malthus to give her a bit of space, but after a pass of the first verse, Steven could not contain himself from peeking around the corner, hands on head in a complex mesh of disbelief; realizing how good the song would become, and how she had changed everything. Her range was voluminous, hitting all of the appropriate high notes without ever sounding strained, and a full throated lower range adding a confidence contrasted against her revealing upper register. After each pass of the song, we were finding more and more subtlety in Jocelyn’s delivery, which prompted us to have her sing backup vocals on two additional songs. She added sublime moments that coaxed even more out those tunes. Jocelyn excused herself after a final pass of the vocal mix, and headed up the wooden cellar stairs, her tiny heels clicking on the treads, as if a tap dancer were warming up. The three of us again looked at each other in silence.

“I feel like we have a complete debut album.” stated Steven, which broke the quiet of the basement; the computer buzz and the water pipes having been the only audible sounds for the last minute.

“Well, let’s put it out!” added Malthus.

“I’m sure I can cobble together a PR campaign, but it’s going to be a tough sell with no live act.” I suggested, hoping to plant a seed that might lead to a live act, which I was sure would be an incredible band to see in person. We had all of the tools and all of the people.

Steven, Malthus, and I decided to take a few weeks break from writing and recording to focus completely on getting music blogs to review the record. It was as I had predicted; with no live act it was hard to build any momentum in the music press. The local paper did a piece on “veteran musicians” of the Mystic scene, but that was the extent of the coverage. We decided to reconvene and write an entire new album based around what we thought Jocelyn could do as the sole singer on a record. After writing sketches of new ideas over two months, the three of us felt we had the framework of a great recording, a specific growth from the first album. There were sixteen ideas, and a bunch of other snippets, things we would casually poach from- similar to an auto mechanic that had a parts car. Deciding it was finally time to bring Jocelyn in to suss out the new material, I volunteered to reach out to her, and to get the four of us on a regular working schedule.

I called Jocelyn on the night of a new moon, secretly hoping the lunar cycle would work in our favor.

“Hey Joss, it’s me Twining.”

“Hey, how are you? I’ve been meaning to get in touch but I’ve been incredibly busy. How are the sessions going?”

The connection was pretty bad for modern phones- it somewhat reminded me of phone calls from my grandparents in Florida on Christmas Day. I had spent approximately some or all of 27 days in my life with them in any capacity. That noise, and their physical distance, always defined their emotional distance. But this was a local call to Jocelyn.

“Fantastic. We have an entire album worth of material, and we really would like you to sing the whole thing, with Malthus adding some counterpoint. But we basically wrote the whole album with you in mind.”

“Wow, I’m honored, and thrilled, but as usual with me, the timing is off. I’m moving to Boston in two weeks.”

After I hung up the phone, I began muttering to myself “shit shit shit Shit Shit SHIT….” Malthus had already done proof cover art, as he was always looking to be one step ahead of the music with the image. His designs were minimalist takes on the visible spectrum of the northern lights, and he found the perfect font for BOREALIS as the working title. Well, that brilliant idea had just gone and walked out the door and cruised the 95 corridor to Boston- we would now have to reconfigure the entire album. Undaunted, we strove for a concise point of completion over the next four months, crafting a wider palette that would include many of the singers from the first album. Brooke Easterhaus, who also sang brilliantly on the first record, was asked to listen to possible tracks that she might feel a fit with. Meanwhile, Malthus had started tracking some rough vocals as we massaged the material into song form. While we were creating a working blueprint for the new record, I decided to give Jocelyn a call in Boston about five months after she relocated. I was hoping we could catch her on a weekend home, where we could squeeze in a few sessions- and at least repeat her singular performance on our new album.

“Hey, how’s it going up there?” I asked “Terrible. I’m working at an Urban Outfitters following people around all day picking up after them. It’s like being a chambermaid for some low grade royal family” she replied, with a resignation of someone who had walked into the first serious misstep in her life.

“Are you going to be in town anytime soon?”

“Yeah, I’m going to visit my mom for three days in exactly three weeks.”

“Do you think you might be able to carve out a few hours and sing on some of the new Borealis tunes?”

“Oh my god, thank you- that is something I desperately need right now…. Just the chance to let loose for a few hours, do something creative. I’m in.”

She seemed genuine about getting into the studio to at least sing on some of the songs, and even expressed resignation about moving after the whole album was written with her in mind. But at this stage of our music career- people who committed themselves to getting “a record deal” and fell short of that goal, nether Steven, Malthus, nor I had any expectations of success in traditional terms, or even finding an audience. We were quite content making the music we heard unfettered by any concept of “success”. The weekend after the Fourth of July holiday she would be back in town, and we booked a session for that Saturday night. As I had anticipated, it was as if she was in the studio the night before, not a six month absence. Pouring herself into the work, she was editing lines as we wrote them, and then singing the revisions immediately.

“no, that just doesn’t work as an idea after the first verse”

“no, that makes little sense in the overall scheme of the song”

“no, that’s really a rebuttal when we need a rallying cry”

Steven had relocated the studio from the basement to the room over his garage for the summer, to access air conditioning. And for the most part it worked out; the bulk of what we recorded was unaffected by room noise. But tracking live vocals was something else entirely for the controlled climate of the room over the garage. There was no way to record the vocals without the mic picking up the air conditioner hum, and the windows had to be closed as well, to prevent ambient sounds from the outside to leak into the live track. Malthus was wiping sweat from his brow with a soaking wet handkerchief. Steven was wiping his glasses on his shirt every two minutes. Jocelyn was unmoved, with no outer emotional reaction to the heat. I am dripping sweat and loving it, remembering that one never has to shovel humidity.

Jocelyn knew what she was capable of, and was cognizant about the flow of words within melodies almost to a savant like degree. The three of us always trusted her on her take, and were furiously writing the song lyrics line by line, word by word, right there in the studio. We would reach consensus on a single line, and she would nail it in two or three takes, and we would write the next line, repeating this process until we had a finished vocal. Unconventional, but thrilling; as the pressure was really on, knowing the limited time frame coupled with the rawness of the arrangements. And again, by the end of the session, we had a completely finished vocal, with background accents and harmonies working in a seamless tapestry. A week later, the song sounded like we had wrestled with it for months, not one four hour studio session.

We continued with the sessions throughout an incredibly hot summer. The feel of the humid wall after sitting for three or four hours in the air conditioned studio was like a re-entry into another world. The music we were creating was our new world; it was that intoxicating. Malthus and I would drive the twenty miles from Steven’s to Mystic listening to the new mixes, and each songs fruition led us to believe we had something special on our hands- and in true Burroughsian fashion, we were exploring “how random is random?” One thought was constantly at the forefront of my mind on those drives home- maybe everything was leading up to this moment, to Borealis. The deep green of the leaf canopy belied the scorched fields between the ancient stone walls of the farms which covered the back roads we traversed. Perhaps we were now mature artists who were becoming the canopy, and not the scorched earth?

The first week of September, I received an email from Jocelyn:

“I’m coming back home, the Boston thing is just not working out.”

It’s tough being twenty and moving out on your own, much less to a metropolitan setting, and even as we knew she was going through an unfortunate moment of growth, I was inwardly thrilled with this prospect. “I say we still keep everything that Brooke worked on,” proposed Steven, “but let’s add Jocelyn to the Malthus songs, and we’ll re-record vocals with her that didn’t seem to be on par with some of the more interesting performances.”

Once she was ensconced in her mother’s house, we began a grueling three nights a week schedule in order to finish the recording in time to submit it to our local music scene’s awards show- which was really just a huge party thrown by the major local music promoters. Their idea for the awards show was “Theme Party” and the theme was “Awards Show”. Local booking agent Caron Morris was the brainchild behind the TAZZIES- in an interview before the inaugural event he was quoted in the local paper:

“I love awards shows!I watch them all whether it’s the Grammy’s or the MTV music awards. I love the whole idea of celebration. So, I thought, why not a TAZZIES show?”

The judges were a collective of booking agents, promoters, and club owners in the NYC to Boston corridor who worked with Caron, and a separate online “people’s choice” balloting. At the show seven or eight bands would do a single number, and interspersed among the performances were awards in categories like “Best Indie Group” and “Best Americana Group” as well as more traditional awards like “Song of the Year” and “Album of the Year”. We were working feverishly in the late winter, the album we titled “Our National Emblem” was submitted for the TAZ Awards right on the deadline., January 31st 2011.

I decided to wear my vintage Beatles Apple Boutique Nehru jacket to the TAZ awards. Dressing in excess was encouraged, and I knew I could set a personal precedent with the evening’s wear. The jacket was given to me by Ricardo Maddalena, one of the cool uncles of my longtime partner Anne Maddalena. Anne and I had been living together for nineteen years by the time of the second TAZ awards, and Ricardo had bought the jacket at the original Apple Boutique in 1969, coincidentally the year of my birth. We had garnered the nomination we were hoping for, “Pop Album of the Year” and felt somewhat confident that we might win. And while the TAZZIES were not about winning and losing, and much more about having fun on a grand scale- it’s always more fun to win. And we did. After Steven, Malthus, and I heard “Borealis”…………… we looked at each other in the same dis-belief that we shared during Jocelyn’s first night in the studio recording “Out at Home”.

“Holy Shit!!” Malthus stated quietly under his breath, so only the three of us could hear it.

“All that hard work paid off, eh Malthus?” I replied just as quietly while we turned on the peastone gravel path. Steven was uncommonly silent. Winning always seemed to bring about some sort of internal conflict within him.

Making our way to the stage for an improvised “acceptance speech”, one of the local musicians with long time ties to the scene yelled out “Where did you get the jacket?” A thick audience laugh followed his witty comment- so perfect for this night of serious/not serious fun.

“Anne’s Uncle bought this at the Apple Boutique in London in 1969. Coincidentally, the year of my birth.”

“How old are you?” came from an unseen voice in the back.

“Well, let’s do the math” added Malthus in a deadpan PBS broadcast voice.

Consequently, much of our acceptance speech was me talking Apple Boutique. Certainly it was a functional facilitation of an awards speech, but I noticed one thing missing. Jocelyn, who I knew was at the event after running into her in the parking lot, was nowhere to be seen. I stammered through the necessary “Thanks You’s” trying to buy a few moments to see if she would make it to the stage.

“Where’s Jocelyn?” I eventually asked the crowd.

And in that moment, after a brisk walk, she skipped down the red carpet- wearing a beige mini dress with high black, glossy heels. The crowd was completely silent as she climbed the stage stairs and joined us. But by then we had already taken up too much time, so I said one last thank you to the crowd, and with both hands, pointed towards Jocelyn, and said “The Voice”. Little did I know at the time it was a moment that would come back to haunt me in Piercing.

After finishing Emblem, we decided to take a month long break before coming back together to take a stab at a completely minimal electro record. The vast majority of the songs Borealis had written featured guitars in traditional or transmuted ways. We decided to eschew them completely. There was quite a bit of static going around in Mystic musical circles as we began rough drafts of our new ideas, following the TAZZIES. It seemed that Jeremy again started speaking for Jocelyn, to some degree. And the impression we were getting was that she wanted to do something completely different from the studio environment. I couldn’t really blame her- the three of us were in full retreat mode from the rigors of a live band, but she was at the precipice of that possible moment in her own life. Why be cooped up in a studio with three “retired” musicians, no matter how creative the environment or the splendid recorded results? And yet, it was strange to hear of this second hand; Jocelyn never expressed these reservations or limitations to me, it was her circle of friends that frequented the Palace that conveyed the information. Perhaps she didn’t understand that the three of us had already come to terms with musical ambitions that had much more at stake than Borealis, and a new “New” beginning was nothing we had not collectively dealt with before. The three of us held a few sessions at

the studio- half-hearted- mostly due to sonic fatigue, but also somewhat because we were fumbling in the dark for the perfect exaltation of our new motivation.

“What do you think of this bass drum sound for this beat” opined Steven during one of the new recording sessions.

“Eh, it’s a bit full, you know? Not the crisp punctuality I think we’re looking for” replied Malthus, a bit reserved.

“Ellery, what do you think?”

“I agree with Malthus.”

“Now you guys are going to gang up on me?”

Steven was in full sarcastic mode, but he would reveal a hint of his true feelings when he reacted that way. I had been witness to it many times over during our years together in Thames and Greenmanville. And I’m quite positive he had lines I would cross that were as equally irritating. I suppose we all had moments of that nature, but Malthus and I simply exchanged glances of disbelief. We were now going to endlessly discuss the tone of the bass drum? It’s not as if we were the Cocteau Twins circa 1989, with unlimited time, drugs, and career choices.

A few weeks later, I received an email from Doug Roosevelt, one of the very successful local musicians who came of age when Steven and I were playing in Thames, our first band that we formed during high school in 1985. Doug was putting together a benefit show for a close friend, Matt Keller, who had passed away suddenly at the young age of 30 years old, from a congenital heart failure that was programmed into his DNA. It was a tragic time, as Doug and Matt had been roommates at a local house, rented by 5 or 6 people at a time during the early nineties when the Gulf War and the first Bush recession forced those of us in Mystic even closer together in an effort to survive. Anne and I, along with two long-time friends, had held the initial lease on Station House, beginning in December of 1991. As the years went by, and people could afford to move into an apartment without 4 other roommates, a next group would fill the void as those kids were trying to gain independence. Doug and Matt were part of the last phase at Station, and that moment held the same immense, interpersonal bond that all of the previous roommates had shared. Everyone was clinging to each other in a concerted effort to be as creative as possible and to stay there. Station House was something that would not exist for the next generation of Mystic kids, of which Jocelyn, Jeremy, and Todd were a part of.

Doug asked Thames to perform at the Memorial Show, which the four members were in total agreement with. It was a long standing trait of uniting under a banner for the common good that defined the two generations of Mystic musicians which preceded the kids now hanging at the Palace. Thames was the band where I first began playing music with Steven, along with Thomas, and Brent . The four of us had an incredible run at the prize, spending nine years together making music that almost catapulted us to the level we were striving for. The band had actually reunited as Greenmanville in the late ‘90’s, running the gamut of the NYC indie scene from 1998 until late 2000, as one of the band’s earliest supporters had become a minor player in the music management circle based out of an office on the Lower East Side. Thames were actually repurposed simply because of the efforts of James Quirk, an NYU graduate working in the management office that handled Jeff Buckley. The Greenmanville concept was that the band would showcase to all of the important NYC players and redeem the Thames season. It was all for naught, as James quit managing the band after three years amid the strife of timelessness and the lack of timely success.

The four of us shared an easy camaraderie that occurs when creativity and close living quarters are enmeshed over decades. The Thames practices were fluid and furious; the details that made the songs come to life in the first place were being heightened by our musical and personal growth. On the night of the show, I was curious to see which of the next generation would come to see if all the stories I had told them over the years of Thames’ “prowess” were simply overblown memories of a past failure. Surprisingly, the audience had swollen to near capacity by the time we went onstage, and it was impossible to gauge the extent of attendance. Thames were in peak form, an elastic time travel which only further revealed the depth of the songs- and on this night, the long wished for ending of an incredible effort came to fruition. The applause was deep and genuine, with a touch of a goodbye that had never previously materialized. There was no nostalgia.

After packing up the gear into the van, thinking that very well could be the last time I ever play in a live band again, I head to the outdoor patio adjoining the club. It was a sweltering July night, and after changing out of the gig clothes which were soaked in sweat, I was surprised to find Jocelyn waiting for me outside. I hadn’t seen or spoken to her in over three months, so it was nice to see that she made the effort to see Thames play.

“You guys were incredible! It seemed as if you had never even stopped playing together.”

“Thanks” I replied with a coy twist of my head. “Now do you believe me?”

I let out a chuckle, hopefully assuring her that I was as deprecating about Thames as anyone, but that we were as earnest as a young band could be when we were active. We took ourselves very seriously; but that was a function of putting your entire faith in the power of the songs. It was how we defined ourselves.

“How are you doing, what are you up to?” I asked with genuine curiosity. Other than her time spent in Boston, this was as long of an interruption in our working relationship since she first walked into Centraal.

“I’m not really doing much of anything. I got a job at the new senior housing complex in town, working with the dietary department making sure everyone gets their pills. And I moved back into my Mom’s house… which is…. daunting. I’m as much of a pain in the ass to her as she is to me. But I love her.”

“Borealis are working on some new material. No guitars this time, just machines and programs.”

“How’s that coming along?” she replied, with a touch of distancing herself from the topic.

“Ok, I don’t think we really know what we’re shooting for yet, and there is a bit of sonic fatigue.”

“Yeah, I know what you mean; I was totally burned out after the rush to finish Emblem. I didn’t even want to sing along to the radio.” She had a nervous laugh before continuing with the train of thought.

“I’m sorry I didn’t stay more in touch with you after the record was done.”

“Hey, that’s ok. We made some incredible music, and I couldn’t be more happy with Emblem; it’s the record I always wanted to make. I don’t even care if anyone ever hears it again, I know I can listen to it, and be instantly back in the studio with you guys and feel that rush of excitement.”

That was the truth. Things change, circumstances shift; even Thames came to an ugly end. The four Thames members were, after a time, able to manage to become closer friends following the conclusion of the group; but normally- these things end badly. At the same time, I had recorded nearly every single piece of music she had ever sung on or written. We had a fantastic working relationship, and she always seemed to push through an issue with a single minded determination that belied her laissez faire social stance. She had guts; a quality not every young musician is blessed with.

“I just didn’t want to be cooped up in the studio all of the time. I think I’d like to do something else, but I don’t even have an idea of what it could be. I’m still trying to wrap my head around it.”

“Yeah, I kept having Jeremy come in to the Palace and tell me how disappointed you were in the results, that the reverb bed wasn’t appropriate…. I would have rather heard it from you, but you know how

he likes to slip into his Asshole Costume and poke at people with a hot match head…”

I replied, trying to contain my disappointment in not hearing it directly from her. Jeremy was a singular talent, to be sure, but he loved to get under peoples skin just for the reaction. He himself didn’t even believe half of the bullshit he’d spew, as long as people were uncomfortable.

“I never told him to tell you that….”

“Look, I know what the recording experience was like for all of us, and its fine….”

She interrupted me before I was able to complete the thought.

“I totally enjoyed my time in the studio. Sometimes I would get a little irritated because I don’t have the technical skills you three have, and maybe not enough of a musical dialogue to get my point across. But I’m very proud of how I sang, and proud of the record.”

That was a relief, and it sounded as genuine as she could’ve been about it.

“Look, I just want you to be happy.” I told her.