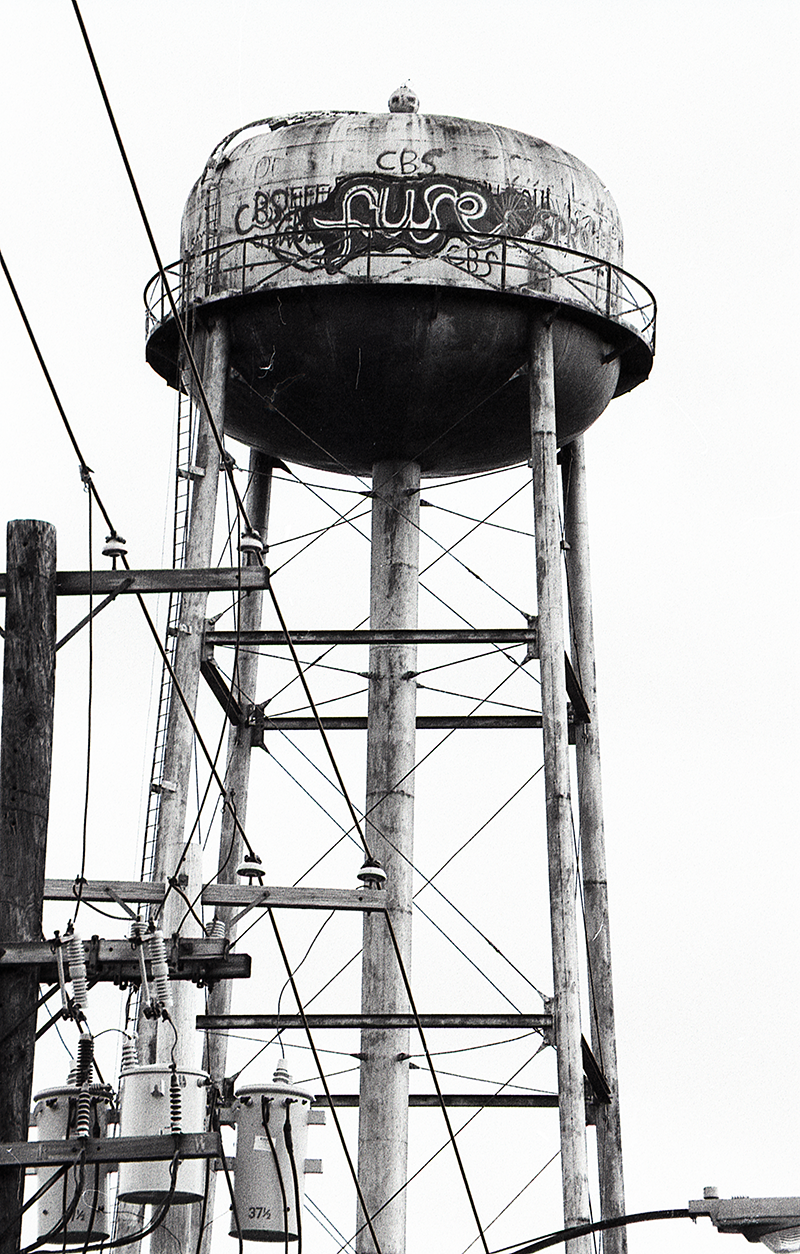

Welcome to the first installment of Mystic Mythology: Skateboarding. During the late 1980s and early 90s, Mystic Connecticut was a bustling hub of skateboarding activity. The merchants hated us, the jocks and jerks wanted to beat us down, and the cops did their best to arrest us. It was kind of an ass-backwards paradise for us punk-rock misfits and I don’t think any of us would have had it any other way. *Please note: some of the details here have been blurred, not for the purposes of artistic license, whatever that means, but due to the fact that I wasn’t taking notes back then, my only access to photography was an OLD Kodak Instamatic, and, quite frankly, I’m getting old. Welcome to part one.

When I turned 12, way back in 1980, I got the one and only thing I wanted for my birthday; a plastic yellow skateboard. It had translucent yellow wheels, loose and loud ball bearings, a tiny kick-tail, and an even smaller pointy nose. I saw it in the Benny’s department store in downtown Groton near the bikes my parents couldn’t afford and I became obsessed with it, pestering them every time we stepped into that store.

After months of begging, cajoling, and promising that I would be careful to not hurt myself, my fantasy of becoming a skateboarder became a reality. On the last day of November, that little skateboard was mine. It did, however, come with a catch, I could only ride it if I promised to wear a helmet. I was crestfallen. If that wasn’t enough, my parents, without consulting me, had gone ahead and purchased a helmet for me and it was quite possibly the most hideous thing I’d ever seen. Instead of an actual Pro-Tec skateboard helmet, my parents purchased a Cooper SK 100 hockey helmet that looked like it was made out of plastic milk jugs. Imagine, if you will; an awkward husky kid from a trailer park, wearing off-brand shoes purchased from the Railroad Salvage store and thrift store ToughSkins showing up at the quarter pipe some older kids built while wearing a beacon of ignorant geekdom upon his head. Let’s just say I wasn’t welcomed with open arms.I was determined, though, and didn’t let those gawking teenage boys bother me. Growing up in a trailer park had prepared me for a life of derision. Instead of trying to overcome the perceived adversity, I would walk past, doing my best to ignore the taunts, and head up the hill behind my house to figure out how to ride that useless plastic toy.

On day one, despite countless promises to be careful and not hurt myself, I did exactly that. On day one I learned two very important lessons: what speed wobbles are and what road rash is. My mother was not impressed.

Covered in scabs, but undaunted, I persisted. On day two, the speed wobbles also persisted, but it was on that day that I learned the importance of “run-out.” This gently curving road had two distinct sides to it: the safe side, with sloping manicured lawns, and the suicide, filled with rocks, briars, and trees. On day two, I discovered that bailing at speed onto a nice, soft lawn required almost no first aid, only soap and water.

Bombing hills, surreptitious trips to the quarter pipe, and the occasional trip to a reservoir spillway that later became known as the Fish Ditch was my entire world for the first two years of being a skateboarder. I didn’t need anyone or anything else and that suited me just fine. At the time there was no way I could predict what skateboarding would come to mean to me, what doors it would open, or how it would be the common ground on which most of my adult relationships would be founded. That little, yellow skateboard, after all, was just a silly plastic toy purchased from a discount department store in the submarine capital of the world.