Excerpt from “Young Offender” by Michelle Gemma, published in Post Magazine, Winter 1994

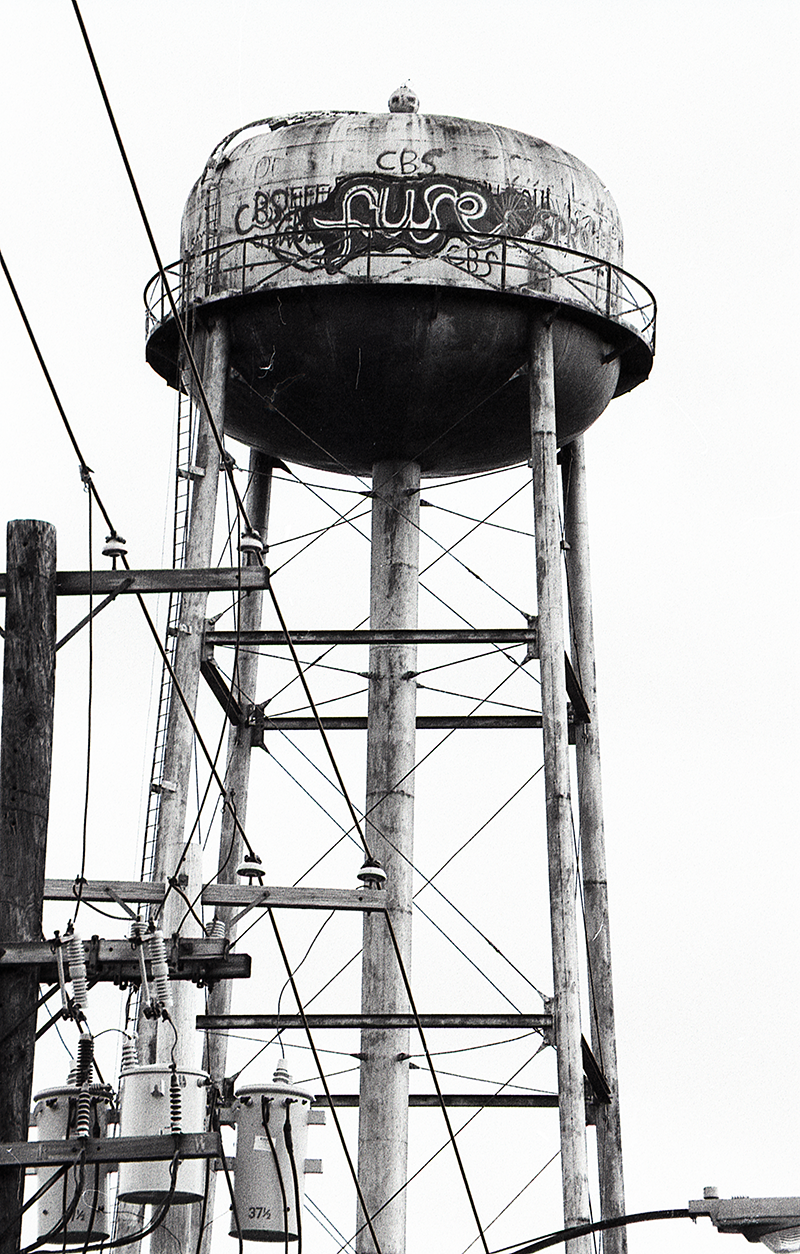

When the media broke the story on Jeff Poprocks last August (1994), there was already a certain amount of recognition surrounding the fuse phantom. Just days before his arrest, one local paper printed the plaintive demands of an eight-year old for the police “to please catch the fuse.” Mystic resident Poprocks’ four month stint as a graffiti artist straddled the towns of both Groton and Stonington, common to most Mystical occurrences. He is currently facing first, second, and third degree charges of criminal mischief as a result of his spray-painting various private and commercial buildings, rooftops, highway bridges and overpasses with his signature fuse. While Poprocks has raised the ire of Mystic property owners, for others, fuse lights our attention like the quick blue incandescence of late night television.

What’s surprising about Poprocks’ case and subsequent effect upon our community is that so many people readily presumed the gang implications of fuse. Locals talked of the certainty of the fuse gang existence in Mystic, and most never questioned it. The actual reality of the graffiti text may have frightened some, and perhaps raised again the suspicion of others that town has changed. The frequent rhythm of the secret coded language marked something of significance, the actual meaning of which we could only speculate upon. When questioned regarding his intent, Poprocks immediately alluded to the conflict of emerging teenage frustration of private self against expressing public persona in a medium at once visible and accessible. Similar polarizations have occurred in the face of our society’s trademark television isolationism, except in the case of the latter, the individual sits at home in front of the television machine with the remote control and does nothing. This may well be an exciting form of communication when taken to the next level of the video game, possibly a convoluted form of an individual art. Graffiti art has always held the same level of fascination as any other individual athleticism: the perfection of the individual will in the edge realm of complete self-reliance. Once the basic technique is mastered, one lives to challenge the self and progress to higher levels of performance.

What the local papers failed to realize and capitalize upon as a positive vibe for town, was the big picture in Poprocks’ case. Fuse is not a gang. Any opportunity should be seized to comment on this. But since most establishment sorts have done nothing to encourage the youth of our town in any real sense, let alone lead them forward into a new era of personal responsibility; the public indifference is not surprising. Instead the youth become criminals, and security forces must be hired to keep them down. Down at home watching television until they go to college, which is not necessarily the most personally challenging option, only the most accessible for those most financially able. As well, television is the most unlikely to encourage self-growth now so that a permanent commitment to Mystic and its cultural future is a reality.

Poprocks is fortunate enough to use the fortuitousness of cosmic timing to his advantage. Since his graffiti artistry occurred entirely while he was seventeen years old, his eligibility for youthful offender status looks good. He turned eighteen days after having been arrested, an occurrence beyond irony and cause for his own personal contemplation and subsequent call to duty. Youthful offender status is granted upon affirmation of many conditions, one of which is the certainty that all offenses occurred while the individual was younger than eighteen. And that fortune may well be his wooden cross to bear. Having experienced the psychological scare tactics in the police’s questioning room after he turned himself in, Poprocks could not bear witness to other graffiti artists. Primarily his outright lack of knowledge as to the others’ identity prevented him from revealing more than he knew. The police were most interested to know who the perpetrators of the defacement of the Mystic Academy building were. Anyone visiting the town-owned building recently is confronted with your more typical adolescent writings on the wall, of local romanticisms and rival town exchanges. Nothing new really, except the scale and all over saturation of the spray paint due to the building’s current limbo status. When the Board of education voted to close Mystic Academy at the end of the 1993 school year, the Town of Groton repossessed the building and its surrounding estate, and is presently trying to figure out its best use for the community.

And here we come full circle. Poprocks’ case moves into its final stages, as he awaits verdict in his application for youthful offender status. He seemingly meets all of the conditions for approval- he has no previous criminal or drug record of any kind. He will plead guilty to all charges against him in a trial without media publicity, and no matter what, he will not go to jail. As long as he is trouble-free until he is twenty-one, his future will not be shadowed by a criminal record. What he will justifiably get from the court system fulfills the monetary implications of his artwork, which includes his own role in community service. A role he has already impressively carved out for himself.