for the Portfire Crew, with gratitude

For the past several years, I’ve talked about writing a memoir a lot. I’m embarrassed to admit this: for all my talking about it, it should be written by now. I also think about writing a memoir constantly, composing sentence after sentence in my head, but never writing anything down. My resistance is strong. It makes lists of reasons for me to stay schtum.

At the top of all the lists: I’ve lived, and continue to live, a messy life. I’m reluctant to share all the shameful bits let alone remember them. People close to me understand that I often play the fool. They’ve seen me create little hells for myself, with my good but naive intentions. I also have quite an index of personality flaws. Nobody but me knows about all my flaws and foolishness, and it’s better that way. I’m intimate with my shadow, but we’re on the down low.

I imagine some potential readers as my high school English teachers, who must be protected from my past and ongoing shenanigans. Other potential readers are my Gen-X peers from Mystic, Connecticut who are connected to Portfire. They already know too much about me, good and bad, so I don’t feel protective of them, especially the ones who find my writing “depressing” and “morbid” etc. If it’s depressing to read about, try living it!

Researching my family history has revealed truly Gothic levels of dysfunction going back generations. It is an ongoing revelation into my own trauma: the context of my messiness, the intergenerational aspects of it. If I’m going to write honestly, I can’t worry about readers who find it “too dark”. I find it “too dark”. It’s incredibly hard to sit with and write about because of its darkness.

I can’t write a memoir. But I can write pieces of memoir…

***

Some context for readers who are not my high school English teachers or fellow Mystic Gen Xers:

- My father, Ben Jones, became famous during my childhood

- He played Cooter Davenport on the hit television series Dukes of Hazzard

- He then served two terms as a Congressman from Atlanta, Georgia

- He is probably one of the largest, if not the top, retailers of Confederate flags

- My father had a rough childhood; he is traumatized and traumatizing

- We are estranged; it is not the first round of estrangement, but it is the final one.

***

Last summer, I made a trip to Portsmouth, Virginia, a small city where both my father and his mother grew up. I found the house that the family owned before the Depression. 732 Broad Street was in an old neighborhood crowded with Victorians. Our house wasn’t Victorian. It was grim and plain and squat. There were fake flowers and faded flags on the front porch. I drove past it a few times, then parked briefly across the street. I wasn’t brave enough to cross the street, to knock on the door.

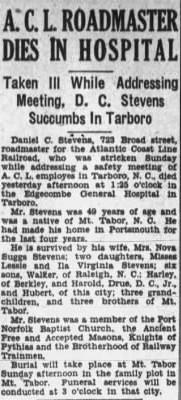

Number 732 was bought by my great grandfather Daniel Stephens, who worked as a roadmaster for the Atlantic Coastal Railroad. He died young of a “cerebral hemorrhage” during a union meeting. His death was the first one in the family to make the local newspapers. There would be many more headlines about us to come.

Daniel and his wife, Nova Jenerette, my great grandparents, had eleven children. Three died in childhood: they lost one at birth, another to cholera, and another to the Spanish flu epidemic. That left two girls, my grandmother Ila and her older sister Lessie, and then six boys, including Lessie’s twin Drue.

Daniel was extremely cruel, according to family sources. Even my grandfather Big Buck Jones, who worked for the ACL with his father-in-law before his death, said he was the meanest man he ever met. And Big Buck was no slouch in the mean department. Daniel viewed his wife and children as property, and he treated them poorly. You can see it in my grandmother’s yearbook photographs. She looked crushed, like she wanted to die. But Daniel died first.

Figure 1 An obituary with the headline “ACL Roadmaster dies in hospital. Taken ill while addressing meeting, D.C. Stevens succumbs in Tarboro.”

Before Daniel’s death, Nova tried to give her girls something for their future: a musical education. Perhaps she saw music as a way out of Portsmouth for Ila and Lessie, dreaming of her girls becoming stars on Broadway or in Hollywood. My grandmother kept those dreams, and she performed for her family and friends all her life. My father made her dreams of a professional show biz career come true when he became a famous actor. (“The greatest burden a child must bear is the unlived life of the parents,” attributed to Jung.)

Nova taught her girls piano and sent them to voice lessons with a music teacher. Lessie had talent, and she was already singing professionally at the time of her death. My grandmother had a beautiful voice too, and she taught her children to love music, just as my father taught me. She also gave him a map that he in turn gave to me: Art as a way out.

After Daniel’s death, the Stephens family of Portsmouth fell on hard times. There were no more singing lessons because there wasn’t enough money for clothes, food, or the mortgage. One story is that Lessie did what she did because she spent some money she shouldn’t have. I can think of a few other plausible reasons for her decision.

On July 8, 1932, Lessie walked from the house on Broad Street to a closed restaurant at least a mile away. She let herself in, spread a quilt out in front of a stove, and turned on the gas. (Did she work there? How did she know where to go and how to get in?) One of her younger brothers found her and called for help. Police and firemen came but it was too late. Lessie had been dead for hours. She was only eighteen.

Lessie left notes, four in all: one for her mother, two for friends, and another written to The Portsmouth Star, the local newspaper. In her note to The Star, she explained, “I’m just so tired of living, so I wish you would be kind enough to say goodbye to all my friends. I have many and I love them all.” She signed it, “Thank you, Les Stephens.” The papers would report her act as “due to despondency.”

One example of how intergenerational trauma works: when I was a teenager, I attempted suicide. Obviously, I was not successful. Instead of dying, I spent the summer before my first semester of college in an adolescent psych ward, where I was diagnosed with major depression. As a condition of release, I had to take antidepressants and attend weekly therapy sessions. There is a lot that I don’t remember about my life, another reason I can’t write a memoir. 1988, when I was 17 turning 18, is particularly hazy. But I do remember that being alive felt exhausting and humiliating all the time, and I didn’t want to do it anymore. Just like Lessie.

***

Radio Singer Killed by Gas; Leaves Note

Miss Lessie C. Stephens Asphyxiated in Portsmouth Inn

Miss Lessie C. Stephens, 18, radio singer identified with WGH, was dead today, the result of asphyxiation yesterday afternoon in the Green Lantern Inn, Rodman Avenue, Westhaven, Portsmouth. A verdict of suicide from illuminating gas will be returned, according to Dr. L.C. Ferebee, Norfolk County coroner within whose jurisdiction the death occurred, a few yards west of the Portsmouth city limits.

Miss Stephens…was discovered shortly before 2:30 o’clock by a nine-year-old brother, lying with her head close to an open oven door, the gas cocks open, and all windows tightly closed. The child, perceiving the situation, called L.C. Hawkins, of Westhaven, who in turn called Norfolk County Policeman J.W. Roundtree, who broke into the place and found it filled with gas. Dr. J.R. St. George and the pullmotor squad of the Portsmouth fire department were called hurriedly to the scene, but they were unable to help the girl. She had been dead apparently four hours, the coroner said later….

Despondency, “just tired of living,” were advanced as causes for the girl’s act, following the finding of a note addressed to the Portsmouth Star. “I’m just so tired of living, so I wish you would be kind enough to say good-bye to all my friends. I have many, and I love them all. I’ll be 19 years old the twenty-third of this month. I have a twin brother of whom I’m very fond and I hope he will celebrate our birthday anniversary as though I were with him. Thank you, Les Stephens.

Other notes in the place were addressed to “Mother,” Miss Sophie Schintzer, and a joint note to William Stubbs and Jack Butler. They were delivered by police, unopened, to the persons to whom addressed. The notes apparently were written in the kitchen where she died…

The body of Miss Stephens will be forwarded tonight via Atlantic Coast Line Railroad to Mount Tabor, N.C., for funeral and internment tomorrow.

To be continued…