Small towns always have secrets. And Pedasi, Panamá is no exception. Guadalupe, the retired Spanish journalist who pretends to be my aunt knows where all the bodies are buried. Sometimes literally. Her investigative instincts are still strong.

She tells me of the rich, old Frenchman who owns a hotel in the hills made entirely of bamboo and who has a penchant for underage prostitutes. Now he is dying of cancer and gets airlifted by helicopter to the nearest hospital for treatments that won’t save him. The bamboo is cracked and crumbling, parts of his hotel tumbling into the turbulent sea.

She tells of the family who owns the most land in and around town. A twisted yarn of greed, pistolas, inheritance as devilish as King Lear. They make my neurotic Jewish clan back in New York seem almost normal.

“The grandfather put his sister in the mental hospital even though she isn’t crazy, so he could steal all her land and dinero.” Guadalupe tells me. “He calls himself ‘El Pato Mas Rico’ because he saw the movie with the rich Donald Duck.

The best antidote to your own fucked up family is someone else’s.

Some nights when the town sleeps, we drive through the empty streets out on a dirt road towards the sea and she points into the dark to a bridge where a tourist was found dismembered over drugs, the pretty low buildings I know are white washed and brilliant in the sun where an expat hung himself.

Bats swoop like skydivers in charge of their own destiny. An owl eyes me from a wooden post, preening in the spot-lit beam of our headlights as we pass.

“Owls are good luck.” Guadalupe says.

But I know they signify change, seeing through people’s actions to their true intentions, death.

In exchange for secrets, a room in her rose red casita surrounded by palm trees, and mango groves, her delicious cooking, I help Guadalupe work the land. A good way to occupy my dream-filled head and steer it away from thoughts of the past and my uncertain future.

I coat palms with calcium (now prohibido because narcotrafficantes use it to mix with cocaine), I chop off old brown fronds with a machete to help new healthy shoots grow, wishing it was as easy to rehabilitate my life.

Guadalupe’s firetruck colored lawnmower is the same model as the one my grandparents had. Pulling the cord, making the motor rev to life brings back lost summers in Long Island, a place I can ever return to.

Their old house in Great Neck is gone now. Summers of gin and tonics, barbeques on the sagging wooden deck, my first real love and I swimming naked in their pool while my grandparents were in Europe. Tequila drunk photoshoots and after smoking joints with laughing friends, our tan legs dipped in the water.

Before all that, my parent’s wedding held before the swimming pool was dug out of the ground, a green cartoon Tyrannosaurus Rex floatie I paddled towards my grandmother’s open arms in, watching my friend almost drown the summer we were eleven.

That pool now fills my mind. I see it as I last saw it: coated in algae, dead leaves floating on the dark surface, a murky lagoon hiding the corpses of drowned birds.

This tropical lawn is vast. A distracting sea of Emerald City green hierba that seems to sprout six inches with every rain storm. These are shoots that resist deforestation, that fight to survive. I am learning from them.

Butterflies flit all around me and the lawnmower’s blades chop off the heads of twenty cornellias at once, the weeds whose wispy white heads hold seeds explode in a million wishes floating through the tropical sunshine.

What do I wish for? That our problems didn’t follow us no matter how far we travel, for a chance at freedom, for peace with the past, for a beer and Wifi.

On my Spanish burner phone, the only device with a somewhat reliable internet connection, my younger brother emails from New York to say my grandmother has an electric wheelchair, she’s running for council in the senior center where she lives now, she has her “mojo back.” But I wonder how many secrets she’s still keeping from our family. I had a front row seat to the deterioration of my grandparents and how much they hid.

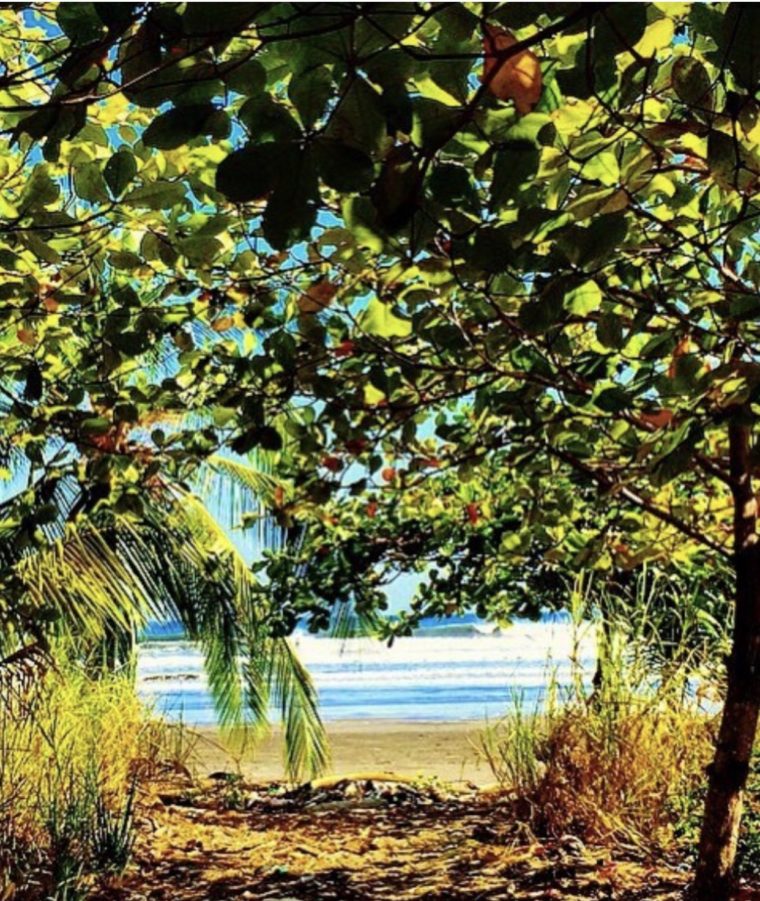

Here, Guadalupe and I explore hidden beaches. We drive over lush hills with the unique curves of peaks once covered by ocean, towards the border with Costa Rica. In an even smaller town called Las Cañas, we perch in a canoe and a local fisherman guides us to a deserted island.

We walk through waist high beach grass, picking marañon and mangos. Our arms fill with fresh fruit. Across the island is a nesting ground for sea turtles, a pure white empty beach curves away into water the same extra azul as the sky. Misty islands rise far out in the sea.

Empty soda cans, amber beer bottles and chip bags litter the shoreline.

“Que triste.” Guadalupe says.

“Sí.” I agree.

“A man rents tents to tourists on the other side of the island.” She shares, “I heard he went crazy and sells drugs now.”

We collect as much garbage as we can. We spread towels and eat our fruit under the shade of a palm. I help Guadalupe, who at sixty-five has a bad knee, walk into the warm waves. We forget for an afternoon how destructive people can be.