“He stands, today, as every day, in a pose of attack. The sword is being drawn as every sunrise arrives.”

A period of upheaval surrounded the removal of the Major John Mason statue in Mystic, Connecticut. The public discourse around the relevance of the memorial grew heated, and local factions clashed. The result of that discourse was the relocation of the statue. The Mason statue was moved to Windsor, Connecticut—the American hometown of the Major—after pressure from Native groups. The controversy around its removal eventually led to a collective understanding by the local population that their society was far different from the post-Civil War era that created the monument. During the decades following the end of the Civil War, many Americans funded the creation of memorials to lost figures in American history who had participated in the colonization of the US. The citizens of Mystic, Connecticut chose Major John Mason as their historical hero. In 1889, the Mason Memorial, designed by sculptor James G. C. Hamilton, was placed at the intersection of Clift Street and Pequot Avenue.

Mason led a coalition of English soldiers and Native tribes in a coordinated attack on the Pequot settlement at Mystic during the Pequot War of the 1630’s. What ensued was the first large scale military operation on American soil. The Pequot were nearly annihilated in the course of one day. Had it not been for the Pequot warriors who resided at Fort Hill, a few miles away, they most certainly would have.

The conventional wisdom about the battle is that hundreds of men, women and children perished at Mystic because of their lack of defense. But Kevin McBride, former head researcher at the Mashantucket Pequot Museum, determined that the Pequot warriors made the trek from Fort Hill to Mystic just in time to drive the remaining combatants off, chasing them through the nearby wooded area to the west, and then further south toward the coves around the peninsula at West Mystic. Archaeological digs have uncovered evidence that the English and Native coalition was not successful in eliminating the tribe, despite the massacre of over 400 people.

Why did the Pequot need to be forced into submission? They sat on the largest concentration of wampum in the southern colonial settlements, the currency that was at the center of the fur trade, which brought both English and Dutch explorers to the area. The Pequot essentially were The Bank of Southeastern Connecticut.

They were also not looked upon kindly by neighboring Native groups, for that reason and others.

In 1636, the Pequot took to the offensive, attacking settlements at Saybrook and Wethersfield. On the first of May 1637, the Connecticut colony ordered war against the Pequot. Twenty-six days later, the attack at Mystic began.

By 1910 there were only 66 members of the Pequot tribe. Today they oversee an international casino empire, and the power which they leveraged in the early 1990s to bring about the removal of the Mason statue was real.

“You cannot alter history…”

Following the tragedy at Charlottesville, I found myself thinking back to 1991, when the residents of Mystic began their discussion about the removal of the Major John Mason statue. Of course, those opposed offered as their central argument that such removal would be “Altering History”. I wanted to remind Mystic about how local debates over the Mason statue had resulted in its relocation. I also wanted to make a public statement about how to move forward with the removal of Confederate memorials. I decided to add a touch of confrontational graffiti to the jersey barriers acting as a replacement guardrail on US Rt. 1, near the Baptist church in town.

WE REMOVED MASON’S STATUE

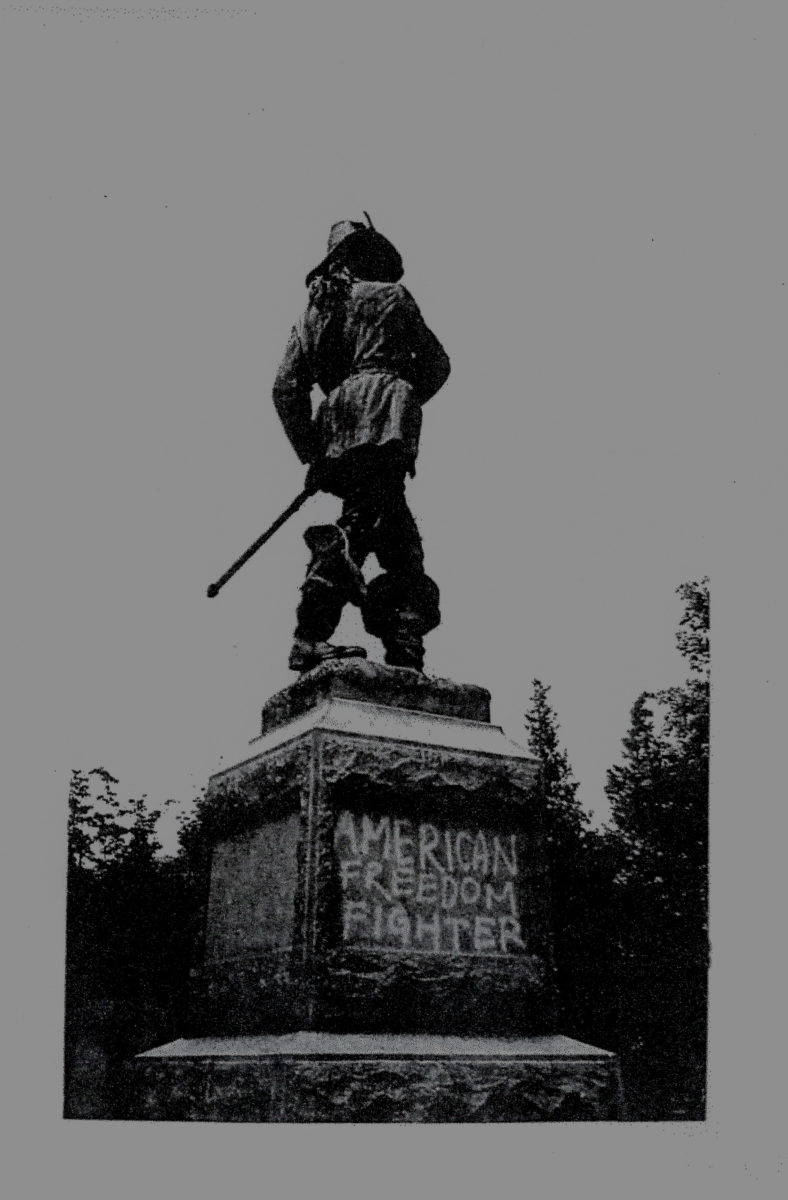

My goal was to send a message that removing controversial memorials had a precedent, right here in Mystic. I was surprised that the graffiti had been covered by slate grey paint the following day. Undaunted, I decided to return two nights later, to restate the message. After all, I painted graffiti on the original Mason statue in 1990:

AMERICAN FREEDOM FIGHTER

That was during the aftermath of the Iran-Contra scandal, a period when the Freedom Fighter moniker received renewed scrutiny. I returned to the jersey barriers and again sprayed in black paint:

WE REMOVED MASON’S STATUE

The message was again painted over and covered up the next day. I was shocked: it seemed that our community wouldn’t broach the topic that we had defined decades earlier, to help assuage another similar issue in another part of the country. A friend told me that descendants of Mason would have painted over my graffiti. But I was still convinced that Mystic could give our fellow citizens a roadmap toward a future that would represent shared values. Confederate memorials could be approached the way Mystic dealt with Mason. We had already established an historical precedent around the topic.

During the writing of this piece, my research has been two-fold: the resistance to change among the local population regarding the Mason Monument, and how our local controversy mirrors the protests against removing Confederate statues from the public square.

“In his effort to clarify and simplify, noted local historian, William Peterson has stated; ‘Many of us have gotten lost in a forest of peripheral issues …. The implications of removing this statue go far deeper than our own parochial interests. The real issue is not about who was right or wrong in the early 17th century; it is not about justice or injustice; it is not about sacred sites or battle sites; it is not about John Mason or genocide. The merits of these points can be argued (or acted) convincingly and emotionally, but to no one’s satisfaction. The fundamental issue is FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION – one of our basic American ideals! The location of the statue may be insensitive by today’s standards but a past generation could not possibly anticipate the moral persuasions and cultural sensitivities of future generations. The site, the plaque language, and the statue are part of the 1889 expression. The reasons that the site was sacred to the Colonists and their descendants may be different from the reasons given by other people today, but they are no less valid.’ Mr. Peterson believes

“That the statue should remain where it is, unaltered.”

“The moral and cultural sensitivities of future generations.”

This is the lesson that the generations before us did not recognize. This is not an accusation. This is a description of an awareness that is an undeniable fabric of modern American life.

The most revealing element was the counter argument from the defendants, as presented by the Mason Foundation during negotiations. The family foundation was surprisingly accommodating at every level of the negotiations, and yet they ended up with no concessions at all.

RECOMMENDATIONS:

We, the members of The Mason Family Memorial Association Inc., being descendants of Major John Mason, do

hereby submit the following specific recommendations to the State of Connecticut.

1. REMOVE ENTIRE STATUE from its present location on Pequot Ave.

2. REMOVE ORIGINAL PLAQUE and loan it to a local museum. Suggested museums: The Indian and Colonial

Research Center, The Mashantucket Pequot Cultural Museum, The New London County Historical Society, The

Mystic River Hist. Soc.

3a. INSTALL STATE HISTORICAL COMMISSION MARKER at the Fort site. b. Promote acceptance and

implementation of Marcus Mason Maronn’s entire proposal for an alternative monument at Pequot Ave. site.

4. RELOCATE ENTIRE STATUE TO HARTFORD, CONNECTICUT. Site on the grounds of the State Capitol or the

State Library.

5a. REBIRTH IMAGE to represent John Mason as a whole person. b. INSTALL NEW PLAQUES as per M.M.M.

proposal.

6. PROCLAIM DAY OF HONOR for Major John Mason.

7. PRODUCE DOCUMENTARY FILM of the entire process for historical and educational purposes.

8. APPOINT M.F.M.A. MANAGEMENT STATUS in regards to J. M. Statue.”

However, their initial stance was confrontational:

“Marcus Mason Maronn has the right idea when he says, ‘We could save a lot of time and energy if the council simply passed a motion to dismiss this entire issue, which has no basis other than the motivation for revenge by certain radical extremists.”

Letters to the editor of the local newspaper echoed those sentiments:

“No matter the right or wrong John Mason acted according to the best thinking of the time. What happened, happened. Our monuments and writings must remain undisturbed.”

“I must be dreaming – having a nightmare, that is. An article in The Day is headlined, ‘Groton OKs loan of statue to Pequots.’ Going back in time a little, the Pequot Indians approached the Groton Town Council requesting that the John Mason statue be removed because it was ‘too painful for (them) to look at.’ Now the Pequots are to gain possession of the Mason statue for their own museum? This was a gutless decision by gutless town officials. Only Town Councilor Frank o’Beirne had a grip on reality, stating that he’s “having a hard time understanding how a statue that was offensive to them (where it is located now) … would not be offensive if they put it in their museum.’ Councilor O’Beirne expressed his concern for the welfare of the statue in an earlier meeting, a concern I share. Just how much time do the Indians spend cruising Pequot Avenue, being ‘hurt’ by the presence of an historical monument?”

The writers of these letters have attitudes similar to those of people opposed to the removal of Confederate memorials in the South. My southern friends like to remind me that the North is not so innocent.

Chicago. Cleveland. Boston. Philadelphia.

I kept turning it over in my mind, what I might have blocked out at the time, due to a myopic focus on my own expectations toward a certain outcome. The point of view that we cannot remove specific memorials was not isolated to a predetermined understanding of Southern values, but was readily expressed by Northerners during a similarly divisive discussion on inclusion and exclusion. And yet, after all of the arguments, the opinions being stated, historical precedents being presented, our community finally removed the Mason statue.

Mystic, Connecticut can show the nation a road map to the future. Our story can teach others how to remove memorials that create hate and division, through thorough negotiations with all sides represented equally.

The conflict delineates history. American history deserves to be a truthful recitation.

source links: indianandcolonial.org

additional edits by rvljones

Reader Comments

I should have known that was you!